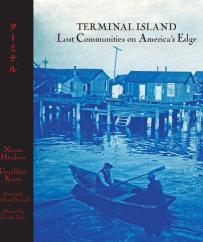

With federal immigration raids and resulting unrest gripping Los Angeles, TPR shares here historian William Deverell’s foreward to Terminal Island: Lost Communities on America’s Edge, by authors–Geraldine Knatz and Naomi Hirahara. Deverell introduces the long arc of the book and praises its excavation of how the forces of migration, prejudice, war, and “ruthless industrial ambition” shaped development—and erasure—of the diverse communities that once called the LA Harbor home. TPR is pleased to share this excerpt from the 2025 California Book Award Gold Medal recipient for Contribution to Publishing, available for purchase from Angel City Press, and anywhere books are sold.

“This book’s dialed-in examination of the creation of the harbor makes for a great capsule study of western American economic, political, and environmental development.”- William Deverell

History is a great tool for excavation. When wielded with skill and dexterity, history unearths the past, lifts people and pathos into view, offers ideas and explanations to fathom mysteries, and then finds safe places to store discoveries and theories. That deftness is well in hand here—the authors of Terminal Island: The Lost Communities of Los Angeles Harbor have gone deep into our shared regional past, carefully unpacking and peeling back time’s layers, and they’ve found a safe, beautiful place both to reveal and care for their findings. In these pages are many lives, many eras, many individual moments and events, all somehow knotted by place, all looped together by the necklace woven of the fascinating history of the littoral zone that makes up the Los Angeles Harbor and one fascinating island in it.

There is much to learn here. Expert on their topics, Geraldine Knatz and Naomi Hirahara fill this book with insight. Long-lost Terminal Island and harbor denizens wander its pages as if sent from a central casting call for salty characters or the far West’s counterpart to Marlon Brando’s Terry Malloy. Railroads and railroaders come, adding a waterfront chapter to their technological conquest of western spaces and western commerce. The army and the navy show up, push a lot of earth and sea around, and re-make space and the economy in the doing. From the world over arrive the fishermen, only to find the boundlessness of the Pacific often countermanded by the sheer pettiness of simple hate and prejudice exhibited by their neighbors, and by laws sprung of fear and meanness.

Alongside the pain that careful histories inevitably illuminate, there are other threads pulled from the Terminal Island past. What is especially impressive here is how Hirahara and Knatz, in text and amazing images curated by Eric Lynxwiler, address the island and the entire reach of the harbor region as a place of breathtaking coastal beauty and the site of ruthless industrial ambition. It’s both, it long has been both, and that intertwining is not about to go away. If anything, this book reminds us of two very important features of the Los Angeles Harbor: it is a thing and a place created at the intersection of nature and culture, and it remains very much so today. The terms may change, the balances may tip here or there, but the inevitable pairing will endure.

The best histories uncover or rethink what has not been known or has not been as well understood as it might be. And the best histories, with grace and subtlety, show how past and present have a seam, an ineffable connection, a relationship that stands. Authors Knatz and Hirahara pull back time in the pages of Terminal Island, and they show us in their excavation an island and a harbor profoundly different from what exists today. Place names are no longer what they were, and they have changed more than once. It all looks different than it did—very different. And yet, Hirahara and Knatz know that the past endures, that its traces are everywhere. Harbor landscape and street names reach back fifty, eighty, a hundred years or more. Decisions made for railroads still provoke consequences in the modern era of cars and containers. Heartaches born of exclusion and internment cross generations, cross the harbor’s water, cross even the ocean.

Terminal Island. Not “terminal” as in “mortal” (though there is that history there, too, as with anywhere, in lives individual and collective), but terminal as limit, boundary, an end point. The name credits the ambitions of railroaders, both to stop their iron at the coastline and to use their railroad as the terminus of grander railroad visions stretching the length of the continent. This book relates that history well, the history of the island as a tiny finale of westering and all that it entailed. But there’s irony here, too, irony that our authors allow to speak quietly for itself. Lives begin on Terminal. Lives are renewed on the island, dreams recast. The tiny communities of the island—East San Pedro, Terminal, and Brighton Beach—become home to travelers from all the world. Some come as seasonal visitors from nearby Los Angeles locales. Some come from Japan, or Scandinavia, or Italy. They may stop on Terminal Island—it may be the concluding site of a long or not-so-long journey. But newness and beginnings are here every bit as much as endings.

Here we meet the tourists, the scientists, the artists, and those turn-of-the-century Southern Californians who constituted the counterculture of their day, circa 1900. Idah Meacham Strobridge, bohemian and bookbinder extraordinaire, forged personal and artistic ties that united Terminal Island with the emergent Arroyo Culture. That could not have been easy—that required a cultural bridge to span distance and different points of view, but she did it. Here, too, is the irrepressible writer, reformer, booster, and bon vivant Charles Fletcher Lummis, coming regularly to the ocean from his handmade Arroyo-stone home, El Alisal. On the island, right against the ocean, Lummis became a squatter in his other house, his beloved Jib-O-Jib. There, he and his family retreated on weekends, catching fish from their porch, and interacting with all those locals, visitors, part-timers. Artists mingled with writers, military men exchanged ideas with scientists, Los Angeles swells came in the summer, Chicago tourists came in the winter. It was scenic, and it was a scene.

Kobei Tatsumi came, too. And so did Kihei Nasu. And so many other Japanese fishermen and settlers. With them and their families came a deep and lasting Japanese imprint on Terminal Island culture, on the political economy of the region, on the very language and linguistic tendencies of the place. One of the magnificent achievements of this book is that the authors have woven the complex stories of the island’s small population waves and changes by introducing us to real people and real lives. All is not renewal and rejuvenation, to be sure. Foreigners—Japanese as well as Europeans and Eastern Europeans—faced trouble in depressingly familiar fashion. And with the Second World War, that trouble multiplied a hundredfold for the Japanese and Japanese Americans living on this side of, and right next to, the Pacific Ocean.

Then there’s the harbor itself, that place and space that wraps Terminal Island in its embrace: the remark able harbor, the harbor as economic engine for Los Angeles, for California, for the West, for the nation. The harbor shows up first more as a dream than a reality, a dream tied taut to engineering and fiscal imperatives, and a dream that takes a long time to come true. This book’s dialed-in examination of the creation of the harbor makes for a great capsule study of western American economic, political, and environmental development.

Credit again to the authors: in a book in which well-considered biographies drive the story, the Los Angeles Harbor is nearly a biographical subject itself. It is not because of its harbor that Los Angeles is where it is. Los Angeles came into being by virtue of its proximity to that modest riparian feature of the landscape, the Los Angeles River. But if we ask why Los Angeles is what it is, we must credit the harbor for a great deal. Ask about Los Angeles growth and metropolitan clout, and its harbor looms in view and emphasis. The harbor’s very creation ushered in the modern period of Los Angeles. That transition from what was to what could be, so ably symbolized by the Los Angeles River’s engineered exit into the Pacific Ocean through the harbor region and right past Terminal Island itself, urges us to study the harbor, its history, its denizens, its human and environ mental complexities and frailties. This is a superb companion to that obligation, a wonderful instance of the insights that come from adroit use of history to dig and thereby discover.

The harbor is connected to Los Angeles by a thin municipal boundary line known as the shoestring. We could suggest that the historical line is as lean. The harbor often skates free from historical perspectives on Los Angeles, for reasons not especially apparent (and this is especially true in the case of a place like Terminal Island, which gets doubly forgotten). The harbor is a region filled with people proud of its history, people who know a great deal about its history, and people who know that this or that self-styled school of metropolitan history knows precious little about the harbor.

We can hope only that this book starts to “thicken” that historical shoestring that connects the Los Angeles past to the harbor and island past. There’s fun and, yes, sorrow in these pages, fun in the discovery of things and people and events unknown, and sorrow in the same. But we can hope that the novelty wears off in the future, that the harbor or the island’s history loses some of its exoticism, but never its message. Here’s the place to start in words and pictures, and we can thank the authors for their efforts at pushing L.A. and harbor together, as they are and should be. Here’s an idea: read the book twice, first for its surprises, then again for raising familiarity with its themes and personnel. Both reactions are warranted.

TPR is pleased to share this excerpt from the 2025 California Book Award Gold Medal recipient for Contribution to Publishing, available for purchase from Angel City Press, and anywhere books are sold.

- Log in to post comments