“Foster’s legacy is not reducible to a single policy win. It is an enduring reminder that leadership and policy challenges are addressed & solved less by slogans than by courageous leadership advancing and institutionalizing frameworks that survive political turnover.”

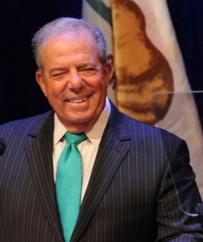

[Publisher's Tribute] A personal mentor, Bob Foster, across two decades of meetings and interviews with our newsletters, is remembered less as a politician reacting to events than as an authentic, one-of-a-kind, systems thinker insisting on preparedness, institutional clarity, and physical reality.

Whether speaking as President of Southern California Edison, Chair of the California ISO, or Mayor of Long Beach, Foster returned to the same uncomfortable truth: modern society depends on infrastructure that must be planned years in advance, paid for honestly, and governed without illusion.

In the early 2000s, in the wake of California’s energy crisis, Foster warned that electricity is not a commodity that tolerates improvisation.

Markets alone, he argued, could not guarantee reliability unless policymakers and the public were willing to absorb the real economic consequences of scarcity. His defense of AB 2006 was not ideological—it both was prescient and structural.

Through his decades of stewardship of environmental planning and policymaking, someone, he insisted, must be responsible for ensuring capacity exists before it is needed, and must have the regulatory and financial tools to do so.

That emphasis on responsibility over rhetoric followed him into city leadership. As Mayor of Long Beach, Foster rejected superficial fixes—whether in budgeting, redevelopment, or port governance—in favor of what he repeatedly called “getting the structure right.”

Infrastructure investment, pension reform, and regulatory reform were not abstract debates to him; they were cumulative decisions that either preserved future options or quietly erased them. Delay, he warned, was itself, a policy choice. A choice that would shift real consequences to the next generation.

Nowhere was Foster’s systems mindset more visible than during California’s post–San Onofre reckoning. As ISO Chair, he framed the nuclear plant’s closure not as a crisis to be dramatized, but as a stress test for institutional competence. Voltage support, transmission upgrades, synchronous condensers, demand response, storage—his focus stayed on how the grid actually functions, not how it is branded.

Renewables, he argued, were not a slogan but an engineering challenge that only worked when paired with planning discipline and emerging storage technologies.

That same pragmatism shaped his vocal opposition to merge the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. Scale, Foster argued, was not a strategy. Velocity, governance, and accountability were, and the notion that consolidation alone could restore competitiveness struck him as emblematic of a broader policy failure: confusing structural reform with symbolic action. A port, or power grid, succeeds by moving goods and electrons efficiently, not by satisfying political narratives.

Across personal conversations and numerous interviews, a through-line emerges. Foster consistently resisted the temptation to promise painless solutions. He acknowledged volatility, capital intensity, and institutional friction as facts, not failures.

Foster’s mindset was consistent: define the market or governance structure clearly, maintain credibility with capital and constituents, and plan for the next stress test—whether that stress takes the form of supply shortages, fiscal downturns, or climate-driven disruption. His approach favored durability over drama, and institutions over impulse.

Foster’s legacy is not reducible to a single policy win.

It is the enduring reminder that California’s most consequential challenges—energy reliability, infrastructure modernization, fiscal sustainability, and resilience—are solved less by slogans than by frameworks that can survive political turnover.

- Log in to post comments