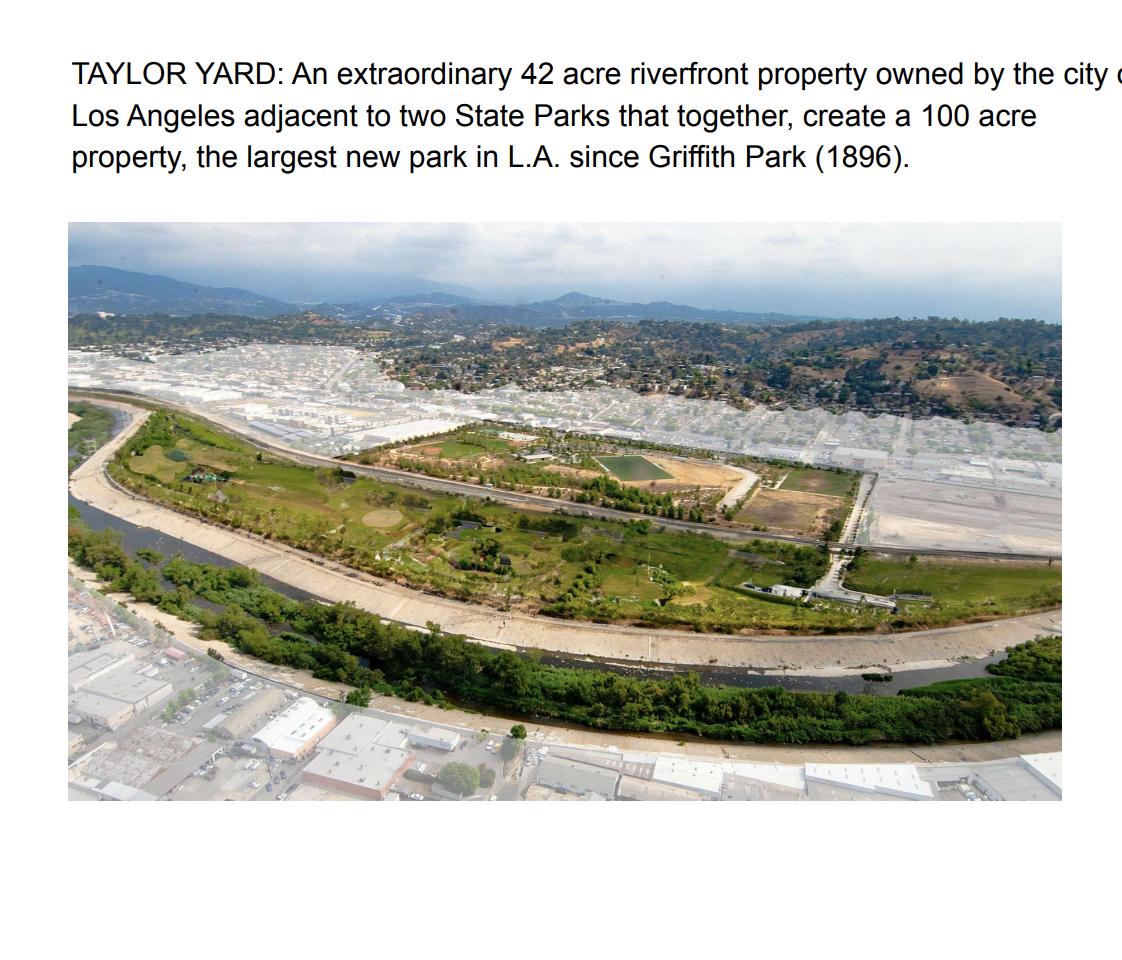

In conversation, River LA’s Board Chair, Harry Chandler, discusses the long arc of the Los Angeles (LA) River’s revitalization efforts and the sobering gap between visionary plans and implementation. Chandler recounts how The L.A. River Revitalization Corporation (renamed as River LA), founded by the City in 2009, with Chandler as its first board chair, was established to advance public and private partnerships along the river corridor with its fragmented governance landscape. Today, River LA’s signature project is the future park-to-be Taylor Yard, a former 100-acre toxic rail site. Chandler reflects on his work leading a multiyear capital campaign, securing naming-rights opportunities for a new city museum, and shaping a broader finance strategy designed to build the pathway—and the political will—to move the LA River from concept to reality, and ultimately, to legacy.

“I’m not as worried that strategy or vision is the challenge […] generally, there’s a common theme: access, recreation, bathrooms, and a bike path. I think it’s funding, and who’s working on it.” - Harry Chandler

Harry, before delving into the LA River, step back to when Mayor Villaraigosa appointed you to the LA River board.

What prompted you to accept that appointment—and what has kept you so deeply engaged in this placemaking effort ever since?

So, a little before meeting with the Mayor, I was working on what became my first book, Dreamers in Dream City. I interviewed dozens of interesting Angelenos and selected about 60 people whom I photographed. One of them was a guy named Lewis McAdams, who had started Friends of the LA River, or FOLAR. He took me down to the river, and I photographed him there. While we were working and talking, he got me interested in the potential of this concrete channel that we’ve all turned our backs on.

Soon after that, he said, “Look, folks in the city would like to meet you, if you’re interested in potentially being considered.” I went into a meeting thinking there would be some low-level people, and instead, Gary Moore, the head of engineering, the Deputy Mayor, and about eight people were there. That told me not that I was so powerful, but that they really needed help and didn’t have the wherewithal to do this project on their own. They were in the middle of working on a master plan for the River, and when it came out, one of the key recommendations was to create a nonprofit…what they called a development corporation.

I became the first appointee, in that case, by Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, and before I accepted the volunteer role, I asked around town for advice: Is this a good thing? Everyone said yes, but warned me of a super complicated project with multiple agencies and governmental branches, so lower your expectations.

Eventually, I said yes. There were 11 of us appointed by either the Mayor or the City Council. I was elected the first board chair, and I’ve been chair for most of the 16 years I’ve been serving.

Jumping forward to the issuance of the County’s LA River Master Plan in 2022, walk us through any contributions to the planning process and what has happened since.

About 32 of the 51 miles of the river are in the City of LA, but 100% is in the County, so we always recognized our job wasn’t just the 32 miles, but the whole river.

About 10 years ago, one of our board members was friends with Frank Gehry. One of our projects at the time was trying to get consistent signage and graphics along the river, even if we couldn’t buy all the land we wanted. We thought it would be fun to have Frank Gehry chair a design competition. When we went to Frank, he said, “No, I don’t want to do that. I want to do the work.” So that started a multiyear project with him and his firm.

The biggest thing that came out of that was the introduction to then–Speaker of the Assembly, Anthony Rendon, whose district is south of LA. We introduced him to Frank, and introduced Frank to many people, including the mayors of all the cities along the river. Eventually, the County came forward and said, “We’ve got land where the LA River and the Rio Hondo intersect. Maybe something could be done there.” Frank looked at it and said, “This is great; we’d love to do something.”

Anthony said, “I’m looking for a signature project before I term out.” He ended up finding about $50 million in State funding. Frank’s team said they would do a cultural center there called SELA, Southeast LA, and that process continues. That also introduced Frank and his team to the County in a bigger way.

When the County did the Master Plan, we brought together the Gehry firm, our firm, and Laurie Olin’s landscape architecture firm out of New York. We were hired to be the glue; to help hold the public engagement and run the meetings. But like all master plans, it’s a great document with great recommendations, yet it wasn’t followed by the County saying, “We’re going to buy X pieces of land,” or “We’re going to change rules to allow development in key ways.”

Still, the relationships we established with the County and other partners continue. The SELA project continues. Frank’s team continues to be deeply involved in design, and though Anthony Rendon is no longer Speaker, that money is still available. We’re hopeful it becomes a reality in the next few years.

Before getting into the Plan and its implementation, reflect on that first meeting with Mayor Villaraigosa. What was exchanged then—and how have they proven prescient over the years?

The meeting with the Mayor was actually pretty perfunctory. He simply asked, “Tell me why you want to do this.” The real warnings didn’t come from him—they came from private citizens who had spent years navigating the bureaucracies that govern the River.

I was coming out of a multi-year film and tech career where things move fast. I was an entrepreneur without much patience then, and I still don’t have much now; so shifting into a world where every big project has meant dealing with slow-moving bureaucracies like the Army Corps, plus the ten or eleven other agencies that control pieces of the River infrastructure was and continues to be a challenge. We’ve also gone through our third or fourth CEO at River LA, each focusing on different pieces of the mission.

But over time, I’ve come to understand the rhythm and flow of this work—think of it like water. I’m no longer paddling upstream. I’m moving with the flow.

Let’s zoom forward to the Taylor Yard project, the largest open-space undertaking since Griffith Park. Talk about the significance of this project and River LA’s involvement.

A little background. One of the first people I spoke with before taking the role was Carol Armstrong, who then led the City’s river projects. She told me, “Of all the things you may work on, the biggest will be Taylor Yard—if we’re lucky.” It was a 100-acre stretch of railroad-owned land along the River. The City wanted it for years, tried repeatedly to acquire it, and hadn’t succeeded.

From that moment on, at every board meeting I’d ask our then–Executive Director, Omar Brownson, “What’s happening with Taylor Yard?” Eventually, Omar helped make the introductions to the sellers, who ended up allowing the State and the City to purchase the full 100 acres in 2017.

Years later, the City came back to us. They knew we had helped secure $50 million in State funds for the SELA project and said, “We don’t have the resources to develop Taylor Yard. We bought it, but we need help with funding. It’s toxic and the remediation is expensive.”

I told them, “I don’t think we can go back to the State for that scale of funding again. But if you let us run the capital campaign, we can raise significant private money—especially with naming rights.” Two or three years ago, after the public engagement process wrapped and the community vision was finalized, the City returned and said, “All right—we want you to do this.”

We now have a formal commitment from the City: River LA is leading the capital campaign, and I’m leading it personally. Forty acres have already been developed by the State as Río de Los Angeles State Park; the remaining land remains barren, waiting for cleanup and funding to build.

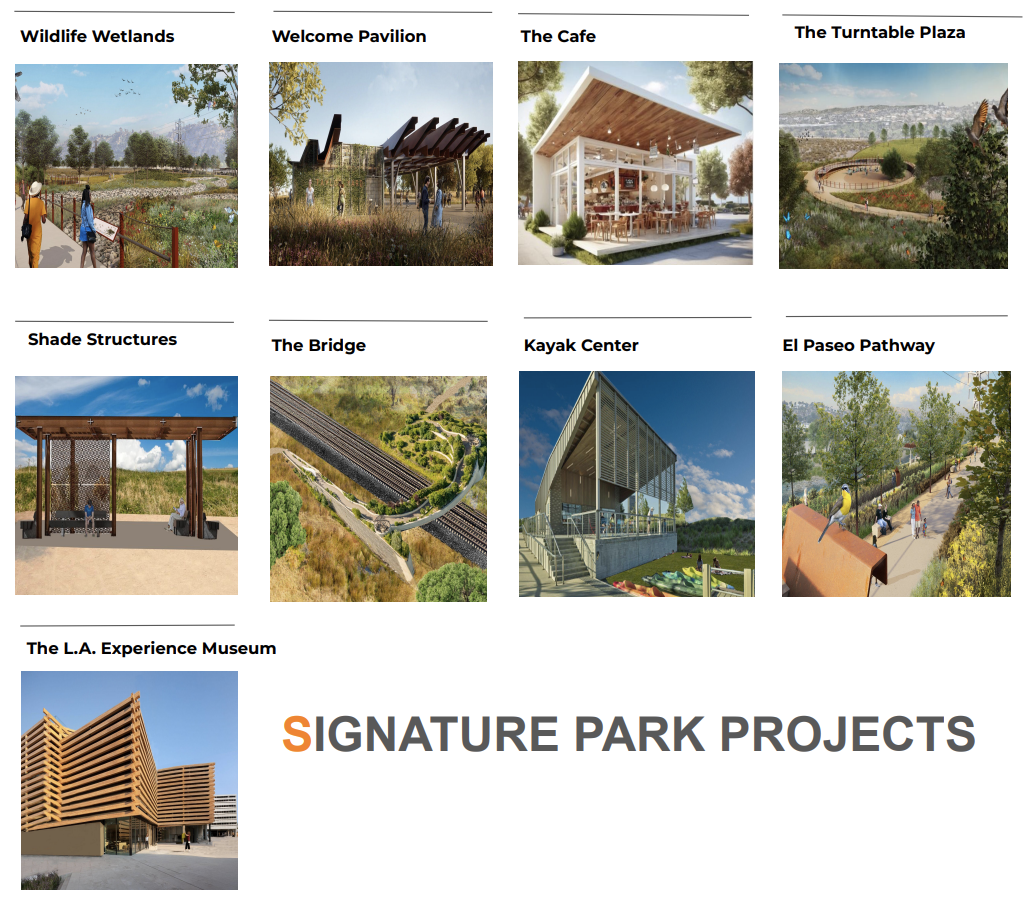

We’ve identified nine great built projects for the park plus a naming opportunity for the entire park, ranging from roughly $6 million to more than $100 million. Working with the City, Hargreaves (the design firm), and our team, we’ve developed a compelling model and presentation. We’re now pitching high-net-worth donors, foundations, and companies to bring the vision to life.

Staying on funding, Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy’s (SMMC) Joe Edmiston once warned us that without a real funding model, the Master Plan becomes “poetry,” something Lewis McAdams would love. Unpack the funding challenge.

Well, you know, I think the reason that, when I first raised my hand and said I’d be interested in joining, was because the City has long been underfunded on a lot of its projects. Doing public-private partnerships with River LA or other NGOs has always been part of their mission, as it is with the State.

In this case, from both the L.A. City Master Plan and the County Master Plan, neither entity has funds sitting aside, saying, “Yes, we’re going to commit to doing all this.” There’s a patchwork of bond money, a patchwork of allocations from other projects that can help pay for pieces of it.

The good news is, if you rewind 16 years to when I started, there have been a dozen big and small projects: water-treatment plants that were finished, micro-parks that FOLAR helped do, and we helped do. There’s been a lot of progress.

But the big moves like finishing the bike path (which Metro is working on), getting Taylor Yard park built out, getting the County land at the confluence with Rio Hondo developed (that the Gehry team is working on)—those are the big moves, and in all cases, it’s a public-private partnership that’s going to make that happen.

The LA River runs approximately 51 miles, 32 of those within the City of Los Angeles, passing through multiple jurisdictions before reaching the Harbor and the Pacific Ocean. Address the challenge of aligning so many agencies, cities, and adjacent neighborhoods around a shared vision.

I’m not as worried that strategy or vision is the challenge. There have been countless community meetings, and by and large, people want the same things: open space, access, and recreation. Yes, one neighborhood may want something different than another, but the common themes are consistent—access, recreation, bathrooms, and a bike path. So when I think about the challenge, it isn’t vision. It’s funding, and who’s working on it.

What, then, is River LA’s role in aligning governance? Are agencies truly maintaining focus and collaborating?

For the most part, it’s working fairly well. The people who really control the River: the County Flood Control District, the Army Corps, City Parks and Rec—they all want many of the same things we and the master plans call for. They’re aligned with the goals. Each agency has its own interests, mandates, and limitations, but when you put them in a room and ask: “Is putting a park here a good thing? Is finishing the bike path a good thing? Can you work on it?” the answer is usually yes.

River LA’s mission, as a small and underfunded NGO, is to be the connector, advocate, and glue—because many of those departments don’t regularly talk to one another. A lot of our work has simply been to convene meetings, push agendas, and be entrepreneurial in a sea of bureaucracies. And that’s not easy.

When you talk about challenges, LA has a governance challenge. Our mayor isn’t as powerful as mayors in other cities; our City Council is diverse; our County Supervisors each oversee massive territories. Getting all of them to focus on the River—and then getting any of them to fund it—is a bigger hurdle than figuring out the vision.

In past TPR interviews, the Army Corps seemed to be a challenge. Is the Army Corps as aligned as you suggest?

The Army Corps is aligned, but they’ve been…you know, sidelined: Trump pulled back their commitment to the Corps, along with many other commitments, partly because it’s California, partly because it was another budget item he wanted to slow down.

The big project the Corps committed to is taking about a mile of the river in the Glendale Narrows area and resurfacing what’s already a soft bottom—enlarging its potential for public access and habitat. Everyone has been working on that for at least a decade, but there have been literally zero shovels in the ground to make it happen.

The bottom line is: personally, you haven’t lost patience.

No, but the Glendale Narrows project is not our biggest priority right now because so much of it is out of our hands. We helped with community meetings and getting city officials aligned, especially during the Garcetti administration, when the City committed to funding part of the project and the Army Corps the rest.

There were two or three different scope proposals: some more ambitious, some less. FOLAR, River LA, and others advocated for the larger one. But then the project fell into the usual Washington stalemate. Very little happened during the Trump years.

To conclude, share River LA’s current priorities.

Let me talk more about what we’re doing at Taylor Yard, because that’s where the most exciting work is happening. I won’t go through all nine capital projects, but I can send you the deck.

One of the least developed ideas when the City first approached us was for a kayak center. That stretch of the River already runs limited kayak trips; it’s about a mile long through the Taylor Yard land, and I’ve kayaked it myself. We’ve now designed the put-in and take-out points, figured out shuttle circulation, and created an operational plan. It’s a project ready for a funding partner—maybe a brand sponsor like Nike, not just individual donors.

Another idea, and the most surprising one, came directly out of community engagement: residents said, “This might be a great place for a museum.” I’ve long worked in the art world with many of LA’s major museums, so that idea resonated immediately. At first, I imagined a traditional L.A. history museum. Years ago, while working with the Autry on an exhibition, I realized L.A. is one of the great world cities without its own standalone history museum. Natural History has an excellent L.A. gallery, but it’s not the same.

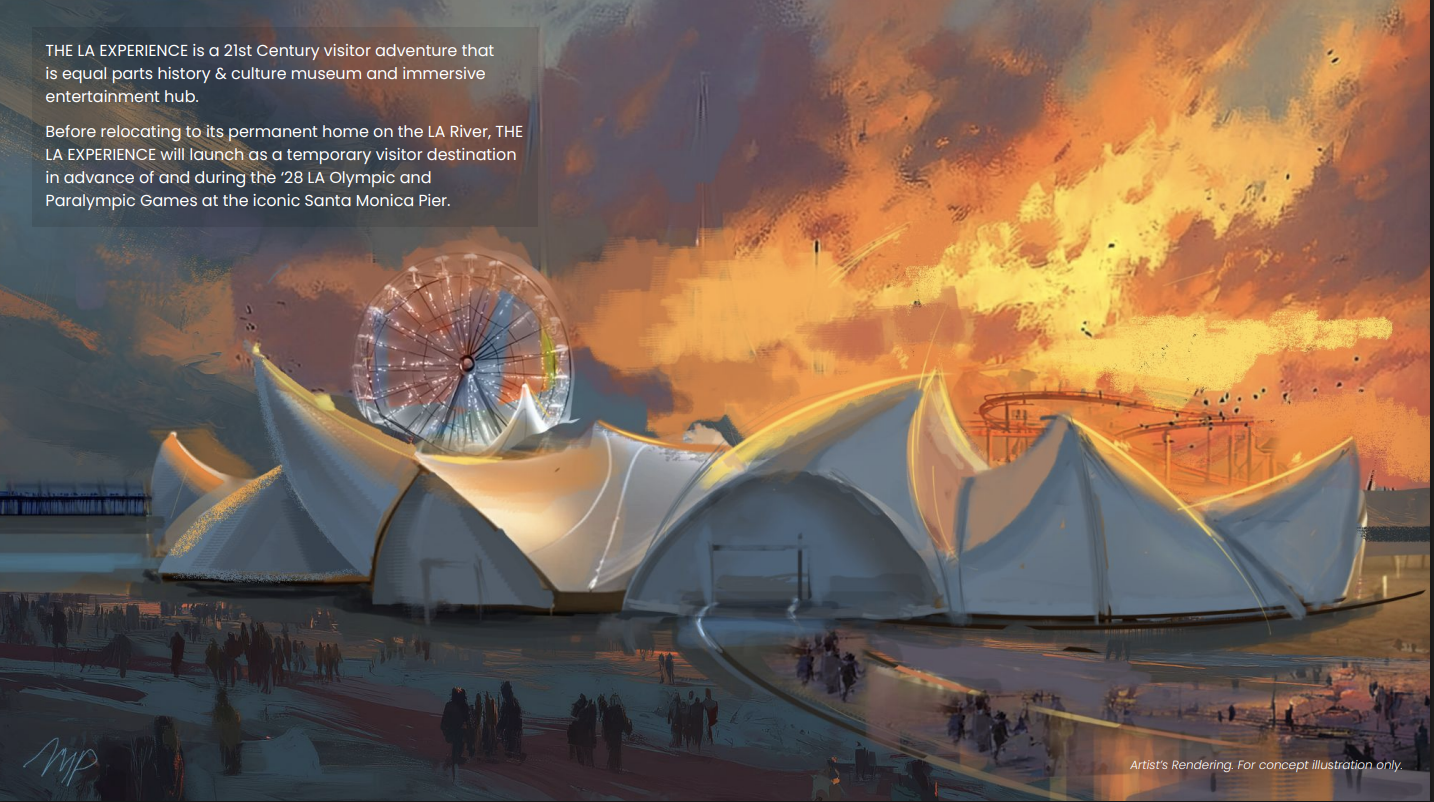

Over the last two years, that early idea has transformed into what we’re calling The LA Experience. It’s a museum about Los Angeles—its culture, environment, sports, entertainment, and music—but told through immersive storytelling instead of objects on walls. It’s more flexible, more engaging, more interactive, and better suited to LA’s identity. The museum directors of the Autry, National History, and Huntington, whom I’ve spoken with, are enthusiastic. We’re not waiting for the permanent museum to be funded to get started, but we will be launching a temporary 40–50,000 square-foot version in summer 2028, during the Olympics, right next to the Santa Monica Pier. I’ve already secured the space from the City of Santa Monica. It will serve both as a fundraiser for the permanent museum at Taylor Yard and as a major River LA fundraising engine—bringing in several million dollars.

We’re now pitching major international brands to be the lead sponsor. There is real enthusiasm because we can offer not just a highly visible sponsorship and branding opportunity, but a unique hospitality venue on the sand, which will likely be the single most visited tourist space in the Southland that summer. It’s a powerful way to debut something that will ultimately become a permanent landmark along the LA River.

I should ask—what could go wrong?

What could go wrong? Well…any big civic project has a hundred people who want to slow you down or tell you it can’t be done. But I’m fortunate—I’m an eternal optimist. I have the time and energy to keep pushing. This is my day job now, so I’m not juggling conflicting priorities.

With my board and our Executive Director, Kate Moulene, I’m hopeful we can create some truly great, lasting legacies for the city.

Editor's Note: The following visual materials were shared by Harry Chandler to accompany our interview.

- Log in to post comments