Abstract

Using a new dataset of eviction records produced through the Tenant Power Toolkit in Los Angeles and interviews with affected tenants, I trace the role of corporate landlords in driving new geographies of Black eviction. With novel access to both tenant and landlord information, we are able to identify landlords’ surgical and deeply disproportionate eviction of Black tenants from neighborhoods with few Black residents. I find that the largest corporate landlords – national Real Estate Investment Trusts – are central in the enactment of these eviction patterns in LA's post-pandemic housing market. Innovations in corporate practice in screening and eviction which responded to the risk and regulatory environment of the pandemic further contributed to saddling these Black tenants with disproportionate rental debt, redoubling the extirpative character of Black tenancy. I conclude that eviction comes to function as a central mechanism for producing and enforcing the racialized socio-spatial order and that collective organizing for tenant power centering Black life and the protagonism of tenant-debtors is necessary to change that order.

Introduction

Eviction is a structural aspect of capitalist housing markets (Soederberg, Citation2018), with disruptive and deadly consequences for those who experience it. Eviction has immense consequences for tenants’ mental (Hoke & Boen, Citation2021) and physical (Hatch & Yun, Citation 2021) health, destructive impacts on the health and stability of communities in which it is a common phenomenon (Schwartz et al., Citation 2024), and often culminates in dramatically elevated risks of premature death (Graetz et al., Citation2024; Tsai, Citation 2024). Eviction is also a singularly important modality of unhousing, with homelessness being an increasingly deadly condition (Fowle & Routhier, Citation 2024). It is also a fundamentally racialized, and racializing process. Black renters are radically disproportionately affected by eviction (Graetz et al., Citation 2023), and eviction plays a key role in the formation and structuring of the exploitative conditions of racialized housing submarkets (Crowell, Citation2022; Teresa & Howell, Citation2021). Eviction operates both formally through the juridical and law enforcement apparatuses (e.g. court evictions), and informally as the outcome of extralegal landlord practices (Gromis & Desmond, Citation 2021), a key node of the “the state-sanctioned and/or extralegal production and exploitation of group-differentiated vulnerability to premature death” (Gilmore, Citation 2007, p. 247).

Previous research has been limited in investigating racial disparity in eviction either (1) without any data about the landlord entity who filed the eviction or demographic information on the tenant being evicted (e.g. Nelson et al., Citation 2021; Sims, Citation 2016) and thereby confined to analysis of the coincidence of race and eviction within a neighborhood, (2) with tenant demographic data but without analysis of the role of specific landlord typologies and practices in perpetrating them, linking households to evictions Footnote 1 (Graetz et al., Citation 2023), or (3) with information on the filing entity but without information on the tenant being filed on, restricting analysis of the racial dynamics of corporate eviction practices to the neighborhood (e.g. Leung et al.Citation 2021; Raymond et al., Citation 2021; Teresa & Howell, Citation 2021).

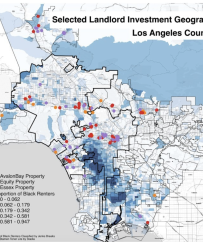

This study employs a mixed methods approach to investigate the role that large-scale corporate landlords play in enacting racialized geographies of eviction in Los Angeles, identifying new eviction geography that has increased in significance due to the afterlives of the pandemic, which themselves remain entangled in the afterlives of slavery (McKittrick, Citation 2013; Sharpe, Citation 2016). According to data from the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project, more than 3,000 evictions are filed in a typical month in Los Angeles (Anti-Eviction Mapping Project, Citation n.d.). Building on scholarship concerning the role landlord-driven eviction patterns play in both gentrification (August & Walks, Citation 2018; Mah, Citation 2021; Raymond et al., Citation 2021) and ghettoization (Crowell, Citation 2022; Leung et al., Citation 2021; Seymour & Akers, Citation 2019; Sims, Citation 2016;Citation 2021; Teresa & Howell, Citation2021) I leverage access to a new dataset provided by the Tenant Power Toolkit (TPT) in order to investigate the possibility that corporate practices are implicated in racialized patterns of eviction that escape these frameworks. The paper is part of a larger movement-based, participatory action research project that I am conducting with the Debt Collective, a national union of debtors, which is a participant in the TPT.

Through this unique access, I identify a pattern of eviction in which Black tenants are surgically evicted from neighborhoods host to relatively few Black renters, which has thus far been unobservable in other studies. This paper finds that the largest corporate landlords – national Real Estate Investment Trusts – are central in the enactment of “racial banishment” (Roy, Citation 2019) in LA's post-pandemic housing market. I argue these actors contribute to resegregation and “police integration” (Hayat,Citation 2016) through their disproportionate eviction of Black tenants from neighborhoods with relatively few Black renters. Innovations in corporate practice in screening and eviction which responded to the risk and regulatory environment of the pandemic, further contributed to saddling these Black tenants with disproportionate rental debt, redoubling the “asset-stripping” (Woods, Citation 2009) character of Black tenancy in Los Angeles. As this paper shows, Black tenants with precarious employment and low credit scores Footnote 2 who would under normal circumstances be screened out seemingly provided a solution to landlord enterprises trying to defray the burden they might bear from pandemic-related economic disruption. These landlords therefore engage in a practice of “creative extraction” through which economic exploitation and spatial exclusion are converted into profit (Purifoy & Seamster, Citation 2021). Precarious and disproportionately Black tenants experience a subordinate and hyper-extractive rental market that subjects them to both economic and bodily harm. Landlords’ determination of tenant “riskiness” in the screening process for example – compounded by previous histories of eviction and other dispossessions – renders tenants vulnerable to a recursivity of dispossession, serving as racist “evidence” of such “riskiness.” This is an example of what Gilmore calls racism’s “triple duty” in which claims of incommensurable difference secure the conditions for the reproduction of economic difference which are then used as evidence to validate the claims (Gilmore, Citation 2022, p. 114).

- Log in to post comments