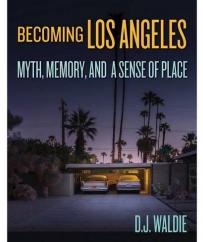

Published in September 2020 by Angel City Press at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic and in the aftermath of civil unrest in Los Angeles and elsewhere, DJ Waldie's new book Becoming Los Angeles is a collection of essays blending history, memory, and critical analysis to illuminate how Angelenos see themselves and their city. In this excerpt, which TPR offers here with permission, Waldie—who in 2017 received the Dale Prize for Excellence in Urban Planning from Cal Poly Pomonal—sets out on an examination of place and explores the contradictions and "sacred ordinariness" that defines Los Angeles.

Becoming Los Angeles

"From its Catholic past, its racial hybridity, and its cycles of boom and bust was fashioned the sinister double that haunts twentieth-century Los Angeles—a city of terrible allure and perverse enigmas. As Eve Babitz quipped in Slow Days, Fast Company (1974), “In Los Angeles, it’s hard to tell if you’re dealing with the real true illusion or the false one.”—DJ Waldie

INTRODUCTION

Dreams So Heartbreaking

A FEW DAYS AFTER MY BIRTH in 1948, on a smoggy, mid-September Wednesday, I was brought home to the tract house in Lakewood my parents had bought in 1946. To be born into that kind of house in that kind of neighborhood hadn’t yet become a suburban cliche The torrent of newcomers to post-war Los Angeles, propelled by defense spending and dreams, hadn’t yet reached flood stage. I lived a boy’s life there, among white, working-class kids whose accents were colored by the border south from which their parents had migrated to assemble planes at the nearby Douglas Aircraft plant. I absorbed old habits that assumed white privilege and others that were so new that my parents and their friends hardly had the language to name them. They would have to read the ads in the Los Angeles Times to know what they wanted. This was not a better time, nor was Lakewood a perfect place. Still, I wish I could hand on, with no inheritance of exclusion, the charmed life that had been given me, with such thoughtless abundance, as a child of suburban Los Angeles. I grew up to write about it. I’ve tried again in this book to understand what it has made of me.

Everything Missing

When we talk about Los Angeles, we mostly dwell on what has been made of its original elements—its earth, air, and water—and much less on how the city shaped those of us who live here. The form of Los Angeles, critics told us, is grotesque or it’s contemptible, and its incoherence ought to be considered a warning and not a model. Angelenos have heard so often that Los Angeles is counterfeit, and the unreality has rubbed off on us. When faced with the homelessness we’ve found in ourselves, we prefer to talk about the climate. Except for the sunshine, the Anglo possessors of the city after 1850 found little here they recognized as the basis for a home. Mid-nineteenth-century Los Angeles was a collection of things Anglo immigrants missed—year-round rainfall, regular seasons, coal, a canopy of trees, and the fellowship of like-minded, white Americans. Los Angeles was a semi-tropical semi-desert and only semi-familiar. Everything ordinary, in immigrant memory, was subtly estranged. The landscape itself was unnerving. It didn’t face the Atlantic and the European shore from which Victorian culture arrived. Instead, it was the alien Pacific and the end of optimistic American wandering westward. Glamour and dread were born from the city’s terminal landscape and relentless climate—geography turned into psychology.

Boosters pasted myths over everything that they missed in Los Angeles. A desirable Los Angeles was written into existence before it was sold off. More guides, pamphlets, broadsides, and magazines ballyhooed Los Angeles between 1850 and 1900 than there were Los Angeles residents. By 1920, the Chamber of Commerce had circulated millions of copies along the East Coast and throughout the Midwest. Words were the scrim on which the hoped-for Los Angeles of the boosters was projected. It would be The Wonder City, Our Italy, The Mediterranean Shores of America, or a Southern California Paradise, never the indifferent piece of occupied Mexico that stubbornly persisted behind the scrim. To Latinx Angelenos, written out of the Anglo sales pitch, climate mattered less than work, access to housing, and the support of communal networks.

The city of Anglo desire didn’t have a past, and so the boosters supplied it. It was a Spanish Fantasy Past, what historian Eric Avila calls an “ethnic masquerade,”(1) in which the fictional Zorro and Ramona dance the fandango and mission bells call lordly Californios to prayer while shiftless mestizos doze beneath their sombreros. In flattening the city’s history of class antagonism and racial conflict into a Days of the Dons pageant, the fantasy past wrung difference and complexity out of the city’s story. Most accounts of Los Angeles still do, generalizing the city’s particulars into sprawl and spectacle or enumerating a few of its social ecologies or hovering speculatively overhead at an altitude of five thousand feet. From there, Los Angeles could be made to look like America’s dead-end.

These misreadings are embedded in the narratives of Anglo encounters with the city. From its Catholic past, its racial hybridity, and its cycles of boom and bust was fashioned the sinister double that haunts twentieth-century Los Angeles—a city of terrible allure and perverse enigmas. As Eve Babitz quipped in Slow Days, Fast Company (1974), “In Los Angeles, it’s hard to tell if you’re dealing with the real true illusion or the false one.”

Sacred Ordinariness

Despite the attention of interpreters as diverse as Carey McWilliams, Reyner Banham, Esther McCoy, Mike Davis, Joan Didion, and Kevin Starr, the boundaries of Los Angeles remain uncertain. Is Los Angeles a municipal corporation of some 503 square miles? An amalgam of the eighty-eight cities in Los Angeles County, along with the county’s unincorporated districts? Or all of Southern California from San Clemente to Ventura? Not just where Los Angeles is but when is unresolved. “No other city,” former Mayor James Hahn said in 2005, “embodies the future quite like Los Angeles.”(2) Mayor Eric Garcetti in 2014 thought of Los Angeles as “the cutting edge . . . the promised land . . . the future.” (3) Hahn and Garcetti were echoing nineteenth- and twentieth-century citymakers who insisted that the only authentic Los Angeles was the city of tomorrow. Having displaced the present and in flight from its yesterdays, the always future Los Angeles hangs suspended between the commonplace and a place that exists only in dreams. This ambiguity has implications for what Angelenos expect Los Angeles can do….

What’s left out of the picture of a post-industrial economy isn’t just contrary evidence that blue-collar Los Angeles persists. Also missing is the space in the imagination that’s made when we get word of actual conditions from those who have lived them. In that space of the imagination, Angelenos could see themselves standing together for economic and social justice, accountable law enforcement, affordable housing, access to healthcare, and protection of workers’ rights. Similarly, disputes about gentrification could pause to absorb the local knowledges that supply circumstance and nuance to situations where there has been only slogans. Planning for a denser, more connected city could begin by acknowledging the durability of prior choices that still shape the built environment. And by recognizing the informal civic structures their neighbors make and manipulate, Angelenos could see themselves as actors in their own history, armed with strategies to confront the pitiless mask of official authority.

In clinging to outdated images of Los Angeles, too many Angelenos avoid encountering the city as a real place. The results are often tragic. Denied access to the sacred ordinariness in our stories and barred from cherished locales mapped on a skin of memories, talk about Los Angeles turns to exceptionalism. Author and architect Michael Maltzan wondered if Los Angeles has “reached a point where past vocabularies of the city and of urbanism are no longer adequate, and at this moment, the very word city no longer applies . . . . Perhaps it is not a city—perhaps it can only be described as Los Angeles.”(5) If not a city, what have we made? And if Los Angeles is beyond words, what unspeakable thing is being made of us? A sui generis Los Angeles, having muted our ability to imagine it, can be described only in terms of wonder or dismay. We ought to heed other stories of Los Angeles—stories to make the indecipherable city a little harder to see.

Los Angeles, whose geographic, psychological, and perceptual limits have been reached, is at an inflection point. Tomorrow has arrived for a city that saw its true self in the future, but tomorrow has come with unexpected company: the working poor, discarded homeless Angelenos, a shrinking middle class, and the callous hyper-rich. Conditions—environmental, economic, and demographic— that Angelenos thought were fixed are rapidly transforming. How are we to be Angelenos when Los Angeles isn’t exactly “Los Angeles” anymore— not the sum of its cliches, without the option to escape to another suburban utopia and now poised to be reconfigured by climate change, economic dislocation, popular resistance to injustice, and the passing of an Anglo hegemony?

Building Intimacy

To paraphrase urbanist Benjamin Schneider, Los Angeles may be a dream world to the rest of America—an extravagance of “pools and palm trees, of music videos and reality TV, the garages where nerds create the future, the freeways and subdivisions coursing with Tarantino’s kinks and Didion’s neuroses”(6)—but to its residents, Los Angeles is simply the place where they are, as beautiful as it is infuriating. Historian Eric Monkkonen insisted that Los Angeles is permeated with localism, with patterns of living, working, and remembering characteristic of beloved places (7). These enfold the specifics of landmarks, memorials, and lore and have the capacity to be what geographer Doreen Massey calls a locality: a site experienced within “networks of social relations and understandings.” (8) Localities, argues sociologist Kathleen Stewart, draw their intensity from the resonances that linger in familiar scenes, commonplace relationships, and ordinary manifestations, steadily picking up texture and inference over time, until everything at hand becomes “tentative, charged, overwhelming, and alive.” These qualities emerge where “sensations, expectations, daydreams, encounters, and habits of relating . . . catch people up in something that feels like something.” (9)

Despite the expanse of Los Angeles and the distracting effect of freeway travel, wayfinding is possible when coordinated by sites where something that felt like something is remembered. But as author Lynell George cautions, our journey through this city’s contested landscape needs the intervention of indigenous guides and the traveler’s wary trust in them, along with a measure of humility, deference to local customs, a tolerance for puzzlement, and a suspension of assumptions.

Even the myths of Los Angeles should be part of our traveling kit. (Erase the myths of Los Angeles in service to the myth of objectivity and our reality is made less real.[10]) We’re lost in the city—and the city is lost to us—if we prefer a generic Los Angeles that (at best) is an archipelago of lifestyle islands connected by the nowhere of gridlocked freeways. That isn’t the Los Angeles of our dreams, not because the presence of other Angelenos has stalled the fluid motion that was this city’s trade-off for a life in a regime of speed, but because, lately, dreams of Los Angeles have become so heartbreaking.

Inhabiting Los Angeles

This book is a remapping of Los Angeles to know where I am, but it’s a peculiar sort of cartography, not an abstract model but a cloud of associations and projections, apprehensions and guesses, minor knowledges and family legends, as well as lived places both actual and virtual, some unchanging over my lifetime, others evanescent or only provisionally fixed. For author and critic David Ulin, “the very act of living in L.A. requires an ongoing process of reconceptualization, of rethinking not just the place but also our relationship to it, our sense of what it means.” (11) Ulin rethinks on his feet, spanning Los Angeles step by step until the city is felt as a presence. In the immediate and tangible materials of the local, Los Angeles discloses itself, renders traces of its past in aspects of the present, and constructs inheritable traditions. Pedestrian Angelenos—slowed down amid the overlooked and the lowly, “placing memories alongside the lived experiences of being”(12)—are able to interrogate the local “in an effort to drag things into view” (13) and furnish the city with what’s needed to make it inhabitable. Author and environmentalist Barry Lopez, writing about his boyhood home in the San Fernando Valley, took even more from his localism. He found “the ground that propels me past the great temptation of our time, to put one’s faith in despair.” (14) The key, he thought, “is to become vulnerable to a place. If you open yourself up, you can build intimacy. Out of such intimacy may come a sense of belonging, a sense of not being isolated in the universe (15)." With intimacy as the mediator between self and city, we are grounded on the street grid of Los Angeles, implicated in its history, and present in the localities where our individual and communal memories are sheltered. Those memories can be harrowing; they should belong to all of us.

David Ulin has taken note of places where history, memory, and the imagination have recently pooled in Los Angeles. He cites the Los Angeles River and Chris Burden’s sculptural assemblage Urban Light (202 vintage Los Angeles street lamps) as places that are recentering Los Angeles. Places like these touch us and in that contact reveal themselves as the outcome of our lives together and not merely as a backdrop. Fear of contaminating encounters defeated Anglo migrants in the past and still defeats those for whom Los Angeles perpetually shimmers under its too bright sun in uncanny otherness. A critical sense of place is the only antidote, as well as a mode of resistance and a means to repatriate our history.

INTRODUCTION Notes

1 . Eric Avila, “Essaying Los Angeles,”

The Cambridge Companion to the Literature of Los Angeles, edited by Kevin R . McNamara, 179 .

2 . Megan Garvey, “Stem Cell HQ Won’t Be in L .A,” LAT, Apr 13, 2005, https:// www .latimes .com/archives/la-xpm- 2005-apr-13-me-stem13-story .html .

3 . Kate Pickert, “Eric Garcetti Writes a New LA Story,” Time, Mar 20, 2014, https://time .com/31924/eric-garcetti- writes-a-new-la-story .

4 . Greg Hise, “Sixty Stories in Search of a City,” California History, Vol . 83, No . 3, 2006, 8 .

5 . Michael Maltzan, “No More Play,”

No More Play: Conversations on Urban Speculation in Los Angeles and Beyond, edited by Jessica Varner .

6 . Benjamin Schneider, “A Field Guide to California Urbanism,” The Urbanist, Apr 2019, https://www . spur .org/publications/urbanist- article/2019-05-16/field-guide- california-urbanism .

7 . Eric Monkkonen, “Community on the Edge,” The Long Term View:

Community and Isolation, Vol . 4, No . 2, Spring 1998, 27–33 .

8 . Doreen Massey, Space, Place and Gender, 146 .

9 . Kathleen Stewart, Ordinary Affects, 128 .

10 . A point made by David Rio in his introduction to Beyond the Myth: New Perspectives on Western Texts, .

11 . David Ulin, Sidewalking: Coming to Terms with Los Angeles .

12 . Neil Campbell, “Affective Critical Regionalism in D .J . Waldie’s Suburban West,” Beyond the Myth, 87–106 .

13 . Kathleen Stewart, “Cultural Poesis: The Generativity of Emergent Things,” The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research (3rd edition), edited by Norman Denzin and Yvonna Lincoln, 1028 .

14 . Barry Lopez, “A Scary Abundance of Water,” LA Weekly, Jan 9, 2002, https:// www .laweekly .com/a-scary-abundance- of-water/ .

15 . Barry Lopez, “We are shaped by the sound of wind, the slant of sunlight,” High Country News, Sep 14, 1998, https://www .hcn .org/issues/138/barry- lopez-we-are-shaped-by-the-sound-of- wind-the-slant-of-sunlight .

16 . Ismail Muhammad, “Walking with the Ghosts of Black Los Angeles,”

Freeman’s, Sep 20, 2019, https://lithub . com/walking-with-the-ghosts-of-black- los-angeles/ .

17 . Juhani Pallasmaa, The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses, 43 .

- Log in to post comments