In response to COVID-19 restrictions, many of California’s local jurisdictions quickly implemented a variety of initiatives focused on the use of public streets in an effort to give residents and businesses more outside space on sidewalks, curbs, and streets to safely use while abiding public health guidelines. Looking beyond temporary, emergency measures, TPR interviewed architect, urbanist, and Chief Urbanist to the Dutch Board of Government Advisors on the Built and Rural Environment, Daan Zandbelt, for a master class on the Dutch approach to balancing mobility planning and placemaking on city streets. Through the Dutch tradition of design thinking, centering pedestrian use, and prioritizing public space, Zandbelt shares how Dutch streets were “reclaimed” from cars from the 1970s and transformed into the multi-modal hubs as we know them today.

Daan Zandbelt

“We discovered that when we start from the specific demands of transport modalities first, public space is actually the leftover and indeed, there's a scarcity of public space. But there's also logic the other way around.”

“What may be typical of a Dutch approach is that we have very much interaction between government and market. They actually make a map and plan together.”—Daan Zandbelt

The Dutch approach to transportation planning has been often highlighted internationally and globally. Speak to that planning approach and what it might teach metropolitan California and Los Angeles jurisdictions about how to reclaim their streets as public places.

Dutch public space has really been dominated from what I call the ‘heart of the street,’ focusing first on the car, then on public transport, then bikes, parking spaces, pedestrians, and then, if there's any space left, there might be some public space at the edges and fringes before we hit the buildings. We have discovered that, actually, much more can be achieved in our cities by turning this logic around.

Starting from the buildings, how can we create much more pleasant places to live and be by giving way to the pedestrian first, then the cyclists, public transport, and, maybe at least in our urban tissue, have the car be much more of a guest than the main dominator—that's something we've been discovering in maybe in the last 10 to 15 years.

To give context to your views, elaborate on both your background as an architect and urbanist and your appointed role as a chief urbanist to the Dutch Board of Government Advisors on the Built and Rural Environment on spatial matters.

The Netherlands has a tradition of being anxious about being a metropolis. We always try to remain as tiny cities, but actually, we had to acknowledge that we had metropolitan issues and metropolitan problems. So, when I started my practice, we were commissioned by the Dutch government to look at how metropolitan regions dealt with these problems. We first looked at Greater London, then Paris, and then we shifted our focus to the west coast to California for our study.

In the Netherlands, since 1800 under Napoleon’s rule, when the French were occupying the Netherlands, they introduced the tradition of the King’s architect, or the Royal architect, to design the palaces and the ministries of the government. This institution evolved in the post-war period and became much more of a governmental adviser on general architectural matters and how to be a cultural client for buildings. It also became much too much for one person.

So, the single royal architect became a board consisting of an architect, an urbanist, and a landscape architect. I'm that urbanist. As a board of three, we can give solicited and unsolicited advice to our national government and its allies, mainly regional and local governments, and sometimes to market parties. We advise on how urbanization and mobility go together. What's the role of the national state in that? How can we reclaim our streets?

How, operationally, does the Dutch National Advisory board inspire local and regional level spatial planning?

Our board brings practical knowledge to the government for four years, part-time. We advise the national government at three levels. One is more abstract, which is that we give advice on the wide policy of spatial planning, so they give us their policy concepts and we review them.

The second level is that we do research by design. We try to put new topics on the government’s agenda. Our latest publication is about why walking works and promoting more pedestrian life. Four years ago, there was only one civil servant at the national government focused on walking, and now there's a whole department of people trying to stimulate walking as a Swiss Army knife for a lot of societal problems that they otherwise would spend billions on solving.

The third level is very practical. The Netherlands national government doesn't have many projects, but they have a few projects in which they rebuild their train stations and invest in large infrastructure. We’re on the quality boards. So, on a very practical level, we try to enhance these train stations or these highway projects. There we see a lot of these issues that we’re talking about. We see that station areas, for example, are no longer traffic machines, but they become, actually, urban places where it's very nice to meet people and stay for a while. And yes, you can also get onto all these modalities, but that's not the dominant factor.

What have you learned to date about the challenges of allocating in alignment with transport goals—a very scarce public space—sidewalks?

We discovered that when we start from the specific demands of transport modalities first, public space is actually the leftover and indeed, there's a scarcity of public space. But there's also logic the other way around. If you first create public space and create room for pedestrians, then, most of the time, you don't need all those other spaces you thought you needed before. That's partly from a quality point of view, but we even found that it's also true from a mobility perspective

With some help from the University and a traffic consultancy firm, we found that there's a logic between the density of citizens and jobs in a certain area and their mobility behavior. The denser an area, in the Dutch context, the fewer kilometers those citizens produce each day and the larger the share they do by foot, by bike, and by public transport.

We discovered that we have to build a lot of houses and create space for a lot of new jobs, like Southern California too. But we also found that we could use those new houses and those new jobs to change the mobility behavior of the existing citizens and companies because they have an awful lot more choice in the proximity of their house or office and more opportunity to do things by foot or by bike.

In the region of Amsterdam, which has about 1.1 million homes already, they need another 250,000 houses and substantially the same amount of jobs. Even with this addition, our calculations showed us that we could reduce the overall car mobility of the whole region. We could add a lot of extra cars and houses and the total amount of car kilometers goes down. The traffic engineers couldn't believe this. But that means there's a lot of government funds can be funneled to making great public spaces instead of highway construction.

What actually qualifies as good public space in the Netherlands?

Very good question. I think we should put people first. Then, it's important that they have quality to stay for a while. I don’t know the best translation, but it’s a quality of local life—a great place to spend some extra time; a great place to meet one another; a great environment to live and to work in. I think a great public space is not too large, so you can recognize other peoples that are in that space.

The buildings around a great public space are oriented towards the public space. They have what I call a frequent plinth, which means that the ground floor of the buildings, which are oriented towards the public space, is quite varied; so, every 10 or 20 meters, there's another door, another function that is oriented towards the space, whether it’s a house, a coffee corner or whatever.

I think it's good if there's a zone that is neither private nor public—you call it in New York, from Dutch descent, the stoop—a zone for the occupier of the ground floor to be outside while not yet being in the public space. That's a good threshold to get more people out of their buildings before they enter the space.

Nowadays, a good public space is also something that creates an interesting microclimate. I really mean it in terms of climate—a place that can deal with heavy rainfall, drought or heat stress. It probably also has green and water elements in it. Those elements can often be useful to let the space become larger if it needs to be when it's crowded, but can also be contained and smaller when there's not a lot of people, and the green is not part of the public space, but it seems to be.

If I can dwell a little bit further on it. The Dutch have a tradition— if you have a bit of architectural history knowledge, then you probably know the CIAM, the International Congress of Modern Architecture. One of their foundations by Le Corbusier and a Dutch fellow, Van Eesteren, introduced the separation of functions. It was everywhere in the world when it was introduced, but it was definitely in the Netherlands. Van Eesteren, he was a friend with Mondrian, the Dutch painter. They even actually founded De Stijl. The urban plans of Van Eesteren and classic Mondrian paintings, they really look alike. You have big red surfaces that are only residential, then you have some other colors that are business owned with black lines for infrastructure in between, so, separated zones.

But Mondrian moved to New York during the war, and he started to make very different paintings. He made the Victory Boogie Woogie and the Boogie Woogie Broadway, which were much more dynamic interactions of smaller colors. In the Netherlands, we conducted a study called the Metro Mix, and we used this analogy. We wanted to have many more mixed-use areas contributing to these vital public spaces. But we learned from the zoning, and by looking at Manhattan that we need zoning not based on function, but on performance. So, we identified three types of zones: Buzz, Fuzz, and Calm.

I'll explain. The buzz is the avenues running north and south—the nicest places with all the cafes, bars, and shops, and the offices, hotels, and apartments on top. It’s lively during the day, lively during the night, and lively on the weekend. There, you have certain public spaces, of course, where the pedestrian is key. That's one zone, the buzz.

Around the corner, you can have streets with calm. The Brownstones in New York are an example. You have buildings—an office, a hotel, an apartment building—where living and working can go hand in hand. There's more space for green. There's more space for climate adaptation. It's more quiet. But around the corner, you have your buzz.

And lastly, I call it fuzz, because of it being a bit fuzzy. That's the rough side of town. That's where we allow for a bit more light industry, logistics, and more experimental zones. You can also live there, but maybe you have a music studio or catering company at your house, living in an experimental studio or loft. The fuzz requires a little bit more tolerance for noise, for traffic, for danger. The public space needs to be a bit more robust around there.

We think that those three zones can also, in a Dutch context, make our existing cities much more vibrant. It also creates a kind of hierarchy or a different organization for dealing with public spaces. They're not equal everywhere, you can highlight.

How, in practice, do you execute on this vision for public space? Obviously, the marketplace responds to government planning regulations. How is this done in the Netherlands? How do jurisdictions restrain the private market from dictating what the what the Dutch zones become?

What's interesting is that the demand for this approach comes from both the market and the government. They're all actually quite enthusiastic about it because both parties see that we have to build a lot of houses. We can put them either in the landscape on the green fields, or we can put them on the brownfields. A lot of parties see that the brownfields are very good spaces because they have a big demand in the market.

What may be typical of a Dutch approach is that we have very much interaction between government and market. They actually make a map and plan together. I'm not sure if it's very positive, but it's just the way how we do it. We use a very strict land use plan as a mean to get into a negotiation with the market party.

Indeed, the market needs to be regulated. We have social housing in the Netherlands, which is protected as a form of subsidized housing. But we now see, as in some American cities, that light industries are pushed out of the cities when they cannot afford the rents asked by the market parties in the city centers. And so, now we proposed to make in line with the social housing corporations also work corporations that provide subsidized rents in these city districts. It's up to the politicians to decide what type of work they want to protect, but they're now experimenting with this.

VerdeXchange has hosted a number of conference panels to address what we call the Amazon Effect and online sales impact on physical retail outlets. How is e-commerce impacting Dutch city planners’ thinking about their streets, public places, and this urban mix, because most of these commercial deliveries are not likely by bicycle.

They do, in fact, deliver by bicycle and by electric van. And this also relates back to Van Eesteren—who’s a nice guy to keep as a key figure. He was chairman of the CIAM and a professor in urban design— a practitioner. So, the logic of the separation of functions 100 years ago came from, of course, industrialization. The city became a dangerous place that made people sick and had poor living conditions. It was very smart to make spaces with light and with air.

Nowadays, we see, actually, that work has evolved, and there’s two sides. We have work that I call human and work that I call unhuman. Human work has a scale and a level of danger and noise that's acceptable for a residential environment. You can mix it in residential environments, and they are mostly welcome.

But there's still a type of work that is very dangerous, or not dangerous, just enormous in scale; it's not nice to be next to. In our metropolitan regions, we have to zone into human and unhuman zones. Your port corridor running all the way down to the ports of LA and Long Beach, that's really dominated by an unhuman scale. Don't put new residences there.

Of course, you need to make those two worlds meet. That's what we need city ports for. We need hinges where the logic from the freight trains and trucks are changed into smaller vehicles and transportation modes that are acceptable in our public spaces. We're now experimenting in some Dutch cities with city hubs, where UPS, FedEx and those kinds of companies bring their goods together, and from there, a city distribution company brings it to the door. Other cities let the companies distribute, but they stipulate that they use more bikes and electric vehicles inside the city, and traditional ones outside. So, I think it can mix but there's a level of hierarchy where the goods need to be shifted.

Is there much competition for scarce street and curb space?

No, I don't think so. We should limit the amount of hinder and danger that comes from them, but there's not scarcity of space on the streets. One of the things that we are promoting, for example in our biking study, is that in urban areas, we should limit the speed to 30 kilometers, or about 20 MPH. With that speed, a car cannot kill someone. It can break a leg, but not kill. It makes the bicycles are more advantageous also because the bike is often speedier. Then also, all of the delivery services, like Uber Eats, go by bike in the Dutch context—all of them, it’s faster.

Los Angeles voters have approved investing $100 billion on public transportation infrastructure to build out rail and bus systems. What should the Dutch experience teach Southern California’s planners about how to organize new mobility hubs to assure they are more than just portals, but portals to a neighborhood or to a community?

An ideal station has, within 300 meters walking distance, all the reasons why you would choose public transport: work, education, healthcare, shops. We might add a bit of living to the mix, but that is meant to make it lively at the moments when those other programs don't live anymore, at night or on the weekend, to keep it balanced.

The next ring, within 10 minutes cycling, about two miles surrounding the station, that's more of the residential area where people come from. In the Dutch context, we use the bike, but in California, it's not strange to come with a car to the station. Now, I realize that if you compare California with the Netherlands, most people are shocked about how dominant the bike is in our system. But you need to realize that we only did this in 40 years.

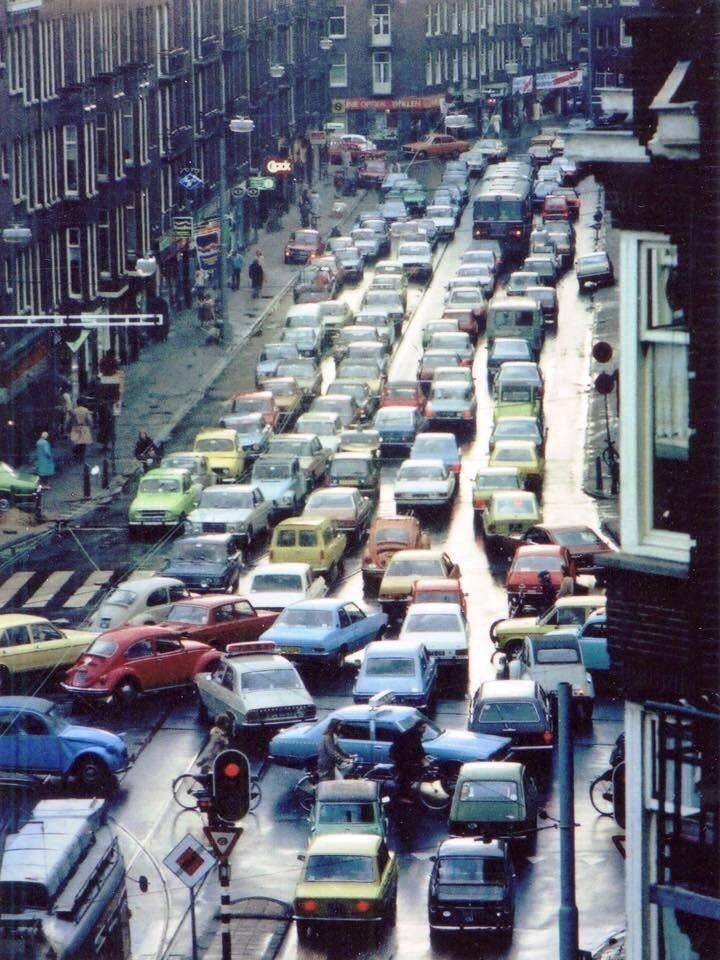

In the 1970s, everybody was using cars in the Netherlands. Cyclists were really in danger, with 3000 traffic victims, mostly on bikes, in those years. There were big protests with cyclists in Amsterdam reclaiming the streets. A civil movement started, and we were introduced to these famous red bike lanes. At the end of the 1970s, there hardly was a biking dominance in our transportation culture.

If you take 40 years, the city of Los Angeles can also make the same shift. You can even reach a Dutch level of cycling. I know sometimes it’s a bit hilly, but your electric bikes can bring you up there, but most of it is fairly flat and can do the trick.

Traffic Congestion in 1970s Amsterdam (Zeilstraat, Amsterdam 1970s)

Before closing this interview, how has the COVID-19 pandemic affected your practice and your advisory board’s thinking about how to insure our cities and streets are more livable?

Well, it's interesting that it has emphasized that the track we were just discovering was an interesting and good track. In Holland, when our tradition of urbanism was born, in the end of the 19th century, it was born because of cholera. There was a pandemic that made people sick. And then first, it was not doctors, it was urbanists that created drinking water city systems and sewage systems, then came the architects with the light and air, and then the function separation. Since Covid-19, the Dutch have rediscovered how important it is that this little circle around your house has all the things that you need in your daily life—outdoor space, a local amenity store, jobs, or schools. And so, I think COVID-19 can help us to make our existing cities better, instead of fleeing them into the countryside.

Lastly, if you were advising your appointing authority on who should be your replacement, describe what characteristics, attributes, skills they ought to have.

They should be a design thinker. Not necessarily a great designer, but someone who can think about multiple good answers to a single question. Someone who can bring forward different argumentations for going left, right, or straight forward. For citizens, politicians, and companies, if they think about the future, they think either everything is possible, or nothing. I think it's our task to create a little supermarket of options to choose between or mix, and it's up to us professionals to show what these ingredients could be. Let them pick and choose and we make a nice meal. It requires a bit of political sensitivity as well that you need to kind of an antenna to see what they’re looking for.

- Log in to post comments