In recent years, issues of housing and homelessness have continued to dominate California's legislative agenda, even more so as the US economy weathers mass job loss and widespread unemployment wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic. Continuing TPR's ongoing coverage of the latest state legislative efforts on housing, Embarcadero Institute president and co-founder, Gab Layton sheds important light for TPR readers on state legislation that—despite asserting the need for housing affordability—in reality, further encourages more market-rate development. With the state on track to build less than 20 percent of the affordable units it needs, Layton also points out the stagnation of state funding for affordable housing.

Gab Layton

"For California to pull itself out of this affordable housing crisis, we need transparency, coordination, and effective, data-driven legislation. We also need to fund affordable housing like it matters."—Gab Layton

The 2020 housing bills currently charting their way through the California Assembly and Senate signal a shift in focus from affordable housing to higher-income housing brackets. This shift is at odds with California’s current affordable housing shortage and homelessness crisis. It is also at odds with housing targets established in a process supervised and monitored by the Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD).

Since 1969 California has required by law that regional planning agencies anticipate their future housing needs and develop plans to address that need. The need is assessed using a cycle of 5 or 8 years, depending on the region. By California code, this assessment methodology must take into account population projections provided by the state Department of Finance, household size data and trends, household formation rates, jobs-to-housing ratios, overcrowding, vacancy rates, and cost-burdening. The need by income level — very low, low, moderate, and market-rate — must be determined as part of this regional planning process. For most of California, the need is approximately 40% very-low and low-income housing units, 20% moderate-income units, and 40% market-rate units.

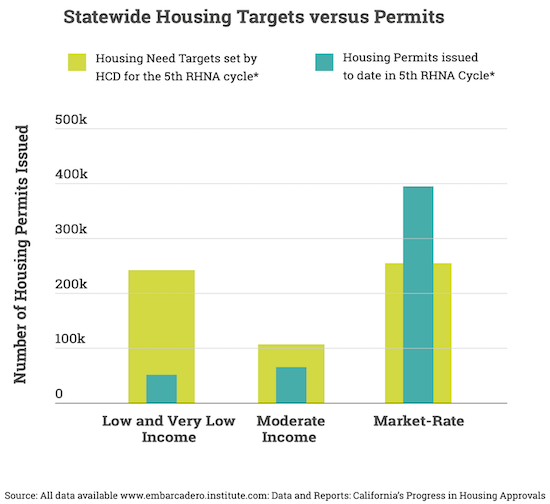

In addition to establishing regional housing needs, the law requires that local governments develop an inventory of land suitable for housing development. HCD ratifies these housing assessments and land inventories, and each April local municipalities report to the HCD on their progress. This process, supervised by HCD, is thorough, defensible and is law. To date, HCD’s annual progress reports show that California is on track to exceed the market-rate housing required in the current housing cycle (due to end in 2023). In fact, 50% more market-rate housing permits will have been approved than required by HCD targets. However, California is set to grossly underperform on very-low and low-income housing targets (see Figure 1).

It comes as a surprise, then, that the California state legislators are authoring bills such as these:

- SB-995 (Atkins, Wiener, Caballero, Rubio) and SB-1085 (Skinner and Caballero) both reduce the affordable housing quota required of developers to qualify for financial incentives, even though California is failing to build affordable housing.

- AB-2345 (Gonzalez and Chiu) increases the “density bonus” available to affordable housing projects. A “density bonus” allows qualifying projects to increase the total number of units as a reward for having a certain percentage of affordable housing units. A bill that offers an increased density bonus to affordable projects sounds positive on the surface. However, the extra housing units are typically market-rate, and that’s where the issue lies. For example, under current law, a 100-unit project, where 25% of the units are low-income, would qualify for a 35% density bonus. It would create 110 market-rate units and 25 low-income units. AB-2345 would increase that density bonus from 35% to 50%, and the same project would instead create 125 market-rate units and 25 low-income units. This is a shift in the wrong direction. The bill effectively incentivizes market-rate, not low-income housing. For every one low-income housing unit, it would create five market-rate housing units (1:5). This ratio sits in stark contrast to the housing need determined by the HCD that claims the state needs to build six affordable housing units for every four market-rate units (6:4).

- AB-1279 (Bloom) overrides the land inventories identified by local governments for future housing. Instead, unidentified “academics” are to determine ‘opportunity’ areas, where housing growth will be directed. AB-1279 (Bloom) also allows developers to pay a fee that is the equivalent of building one affordable housing unit in exchange for the right to upzone land currently zoned for single-family housing (R1) and develop ten market-rate units. This bill, encouraging a one-to-ten ratio of affordable housing to market-rate housing (1:10), once again, contradicts the HCD findings that California needs six affordable units to every four market-rate units (6:4).

- SB-902 (Wiener) similarly creates an upzoning opportunity for market-rate development, allowing the development of ten market-rate housing units in R1 zoning.

- SB-1120 (Atkins, Caballero, Wiener) allows duplex development ‘by right’ in R1, granting these market-rate developments reduced and, in some cases, zero parking requirements.

The bills above all encourage market-rate development, giving away incentives otherwise reserved for affordable housing, even though data reported by the HCD clearly shows that’s not where the problem lies. The left hand of state government (the Assembly and Senate) appears to be operating completely independently of, and at odds with, the right hand (the HCD), as it pertains to housing policy.

Only one bill,

- SB-1299 (Portantino), encourages moderate-income housing. The bill acknowledges current economic realities and the pressure on retail/commercial real estate. It offers an innovative economic incentive for cities to repurpose idle big-box retail for work-force housing - a win for cities and a win for moderate-income housing. The state needs more bills, like SB-1299.

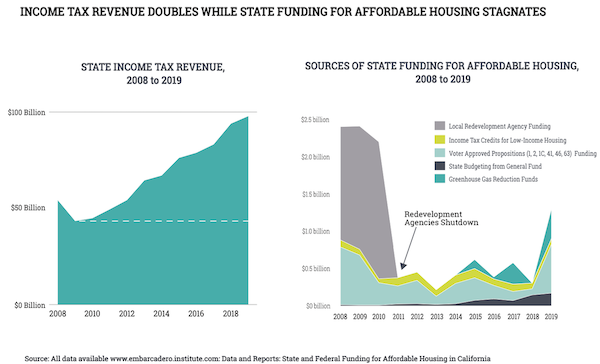

This seeming abandonment of affordable housing in the 2020 legislation exacerbates a decade-long funding shortage for affordable housing. During the Great Recession, the state terminated most of its funding for affordable housing when it shut down the local Redevelopment Agencies (RDAs). At the time, RDAs provided 80% of the state funding for affordable housing through the redeployment of local property taxes. However, facing a budget deficit, Governor Brown froze local redevelopment activities in 2011 and then shuttered the agencies in 2012, diverting their property tax resources to schools and local services to address the state funding shortfall. When the economy recovered, state funding for affordable housing did not improve. This occurred despite a doubling of state income tax revenue in the last decade.

Last year the state collected almost $100 billion in income tax, up from just over $40 billion a decade ago. Meanwhile, funding for affordable housing stagnated despite voter efforts to approve propositions allowing the state government to take on debt for affordable housing (see Figure 2).

The question remains as to why, when the state government acknowledges an affordable housing and homelessness crisis, does it not prioritize funding for it? And why do legislators ignore the data produced by the state housing department and dismiss the legally mandated housing element process? If the legislators don’t have faith in the system they oversee, how can they use the same system to repudiate and chastise local governments for poor performance? Either they believe 60% of the housing need lies in affordable housing (40% low and very-low-income and 20% moderate-income as HCD reports), and then legislation and funding should fall in line accordingly, or they believe California should simply focus on market-rate housing. If that’s the case, the legislators need to dismantle the regional housing needs assessment process.

As it stands, the state is on track to build less than 20% of the low-income and very low-income housing it is said to need by the end of the current housing cycle in 2023. The need for low-income housing will only increase as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. HCD data reinforce that affordable housing is the challenge, yet legislators are focused on the over-achieving market-rate segment. It is past time for the left and right hand to be on the same page. For California to pull itself out of this affordable housing crisis, we need transparency, coordination, and effective, data-driven legislation. We also need to fund affordable housing like it matters.

- Log in to post comments