The fourth annual Rose Award Luncheon held on May 1 at the Rose Garden in Exposition Park celebrated architect Brenda Levin for her extraordinary contributions to the quality of life in LA for more than 30 years. TPR has printed a transcription of the ceremony’s remarks, beginning with Dr. E.C. Krupp, astronomer and director of the Griffith Observatory. Krupp introduced Levin, describing her insights and contributions as a leader during the restoration of the historic structure on the slope of Mount Hollywood. In accepting the award, Levin recounted her journey to becoming an architect and the opportunities that Los Angeles—with its forward-looking culture—have afforded her, particularly as a woman starting out in the field. Levin characterized architecture as a romantic profession, reflecting on the satisfaction she has received in helping to shape the built environment of the city.

Brenda Levin

“The fact that the LA Parks Foundation has chosen an architect for this honor is a testament to the maturation of Los Angeles—acknowledgement that quality of life is synonymous with a city that restores, revitalizes, and enhances its urban form and open space.” -Brenda Levin, FAIA

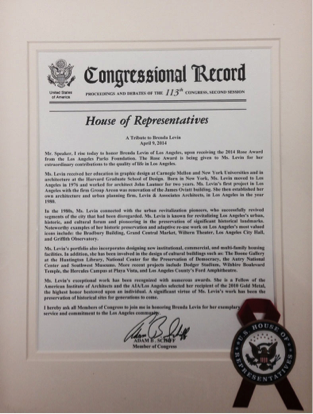

Dr. E.C. Krupp: I am delighted to join all of you among the roses of Exposition Park to salute Brenda Levin, recipient of the Los Angeles Parks Foundation’s 2014 Rose Award.

Previous recipients of this singular bouquet include a US Congresswoman, an enduring and philanthropic actress, and a city councilwoman—all honored for extraordinary contributions to the quality of life in Los Angeles.

Brenda Levin represents another and entirely distinct dimension of contributions. She is, of course, an architect. That means she has a visual impact on Los Angeles, an experiential impact on Los Angeles, and ultimately an emotional impact on Los Angeles.

People quite naturally encounter what she has done—not through her name or reputation, both of which are luminous, but through her craft. They are transported by the environments she has touched, created, and transformed. You feel her impact at the market, at the theater, on the campus, in the chambers of municipal government, in business offices, at the museum, in the galleries, in the temple, in the train house, at the ball park—everywhere, including, for that matter, a public observatory.

All of these enterprises have a public dimension, and many are elemental and iconic components of public life in Los Angeles. This helps explain why her recognition with the Rose Award was not just fitting but inevitable.

Brenda has deservedly received many high-end accolades, and they are understandably architectural awards. She is a leader—a tasteful and pioneering leader—in her field. The Rose Award, however, is presented for extraordinary contributions to the quality of life in Los Angeles. In particular, the 2014 Los Angeles Parks Foundation Rose Award acknowledges her reinforcement, enhancement, and development of the urban, historic, and cultural form of Los Angeles.

So, for Brenda, improving the quality of life in Los Angeles is not just an exercise in architecture. It’s an engagement of purpose and place on behalf of personal and public perspective.

If you look at the map of the projects Levin & Associates has undertaken since Brenda founded the firm in 1980, you see that she has embraced the entire region and left opportunities everywhere to encounter the meaning of this city. She has woven a fabric of dignity, integrity, authenticity, and accessibility into the landscape with these places. Each one is a revelation that makes you understand the worth of the whole.

Now, this award is bestowed on Brenda by the Los Angeles Parks Foundation, and Brenda’s connection with City of Los Angeles parks is particularly relevant to me. Griffith Observatory is owned and operated by the City of Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks and is in Griffith Park. Levin & Associates was a primary resource for and an essential partner in the Griffith Observatory renovation and expansion—a project with not just an international but a cosmic profile.

It was complicated. It was unnerving. It was risky. But it was also sublime. Brenda and her team helped us negotiate the territory. They immersed themselves in a specialized, technologically complex, highly visible, temperamental, and completely public building in Griffith Park to understand its heart and to use that understanding to preserve and transform it for millions of visitors to come, to ensure its heritage, to perpetuate its contribution to the quality of life in Los Angeles, and to help it project the cultural power of Los Angeles to the rest of the planet.

All of us got through that project alive because Brenda is bonded to meaning and value. And in a project like Griffith Observatory, details matter. Brenda Levin is attentive to detail. Please let me provide an example. After we stripped the building down to the original concrete, we had to determine what color it should be. This is not as obvious as it sounds, and it makes a difference. No matter what color the building wound up, it had to be right. Everybody in the Los Angeles Basin would see if we’d succumbed to expediency or bad judgment. The intricacy of Brenda’s process meant she had to guide us through a deliberate examination of 50 shades of white to find the right one. That is attention to detail.

All of us got through that project alive because Brenda is bonded to meaning and value. And in a project like Griffith Observatory, details matter. Brenda Levin is attentive to detail. Please let me provide an example. After we stripped the building down to the original concrete, we had to determine what color it should be. This is not as obvious as it sounds, and it makes a difference. No matter what color the building wound up, it had to be right. Everybody in the Los Angeles Basin would see if we’d succumbed to expediency or bad judgment. The intricacy of Brenda’s process meant she had to guide us through a deliberate examination of 50 shades of white to find the right one. That is attention to detail.

Please let me complete these remarks with one more example of Brenda’s astute vision. Griffith Observatory’s historic north façade is punctuated by a stunning set of massive, ornamented doors and ten monumental windows. Most of the windows had been blocked by interior exhibits—or venetian blinds—from the very beginning of the Observatory, in 1935. Interior exhibits don’t like exterior light, and so we rarely thought about the windows. Brenda, however, saw how those windows could demonstrate the public character of the Observatory and indicate the place is full of life to anyone approaching the building at night. She wanted them to extend an invitation to enter, and she imagined lighting the windows from the outside frames to suggest interior illumination.

Now, Griffith Observatory, if anything, is about the night sky. We want things dark. We want the building dark. We want the lawn dark. We put telescopes out front, and we want them dark. Artificial light is astronomy’s enemy.

So, I was not enamored with the notion of projecting light from the windows out to the front walks and lawn, and I explained my complete dedication to the dark side to Brenda. She, however, already understood these conflicts and consequences, and she mindfully explained what the light would do for the visitor experience. She addressed the conflict of light and darkness with a strategy for restrained, artful photons, and because Brenda is who she is, she made me confident to say, “Let there be light.” And she was right. The place is gorgeous.

Thanks to Brenda, at Griffith Observatory, we leave the light on for you, and I am honored as her client, her admirer, and her friend to present to her today the Los Angeles Parks Foundation 2014 Rose Award.

Brenda Levin: Thank you, Ed, for that generous, stellar, “over the moon” introduction that my late parents also would have treasured.

Ed was an amazing client throughout the long and challenging renovation and expansion project of Griffith Observatory—he never tired of enlightening and expanding the design team’s limited astronomical universe with humor and passion, all the while wearing celestial themed ties, as he is today!

I am truly honored to be here this afternoon to receive the fourth annual Rose Award, and to follow in the footsteps of such amazing, distinguished past recipients—each of whom have made lasting and remarkable contributions to the cultural and civic life of Los Angeles.

The fact that the LA Parks Foundation has chosen an architect for this honor is a testament to the maturation of Los Angeles—acknowledgement that quality of life is synonymous with a city that restores, revitalizes, and enhances its urban form and open space.

As everyone here knows, no great city is without a network of parks. The Los Angeles Parks Foundation is committed to ensuring that our existing parks remain vibrant and that our city becomes greener and healthier by investing in land for the parks of our future.

My journey to Los Angeles was, as most transplants, not a linear one. In fact, I spent my first 30 years on the east coast and my formative years with the expectation that I would find my life’s work in the visual arts.

As a child I grew up drawing, painting, and eagerly awaiting John Nagy’s weekly TV drawing lessons. I took art classes with a well-known portrait painter whose studio overlooked the Hudson River. Although the only child in his nighttime class, I was taken seriously, formally taught, and encouraged in a way I had not experienced in my public school. As a teenager I took the bus across the George Washington Bridge to New York to attend the Arts Students League, surreptitiously changing my clothes to the requisite “black” in the school’s bathroom before class to disguise my suburban roots.

In 1964, when I arrived at college, in the School of Fine Arts at Carnegie Tech, the sheer talent, discipline, and experience of my classmates both challenged and intimidated me. In quick succession, I majored in painting, textile design, and printmaking, finally settling on graphic design. I did once peer into the college’s school of architecture but noticed that there were just two women students who had managed to break through the profession’s historic male gender bias. With the women’s movement not yet fully in bloom, I was not enticed.

That changed substantially by the time, at the age of 27, I began a Masters program in architecture at Harvard, where 40 percent of my first year class were women, an exponential increase from past years. That statistic, it should be noted, was confidence building, but has—three decades later—yet to be translated into any parity in the number of women in senior positions within architecture firms nor firms headed solely by women.

Graduating in 1976, I skeptically but bravely accompanied my soon-to-be husband, David Abel, across the country to Los Angeles. I was, needless to say, a bit apprehensive about becoming an actual resident of sun drenched, sprawling Southern California.

What I came to realize, in short time, is that Los Angeles is actually a petrie dish for dreams—unusually open to experimentation, receptive to adaptation, self invention, new ideas and even women architects from Boston. I grew to appreciate both how transplants like myself were embraced based on merit, and given opportunities that were often beyond the reach of women and minorities in more traditional locales.

I’ve been fortunate to have now practiced for more than 30 years in Southern California, and the personal and professional rewards have been many.

It’s appropriate today, with the Rose Award in hand, to reflect.

Frankly, architecture is a romantic profession. As children we spend hours building imaginary cities, towers, roads, and bridges, transforming ideas in our minds into a physical reality. Seeing something emerge from nothing but our own vision is a very powerful stimulant.

I love cities, their complexity and energy. The belief that I might be able to shape and impact the urban built environment drew me to architecture. I have not been disappointed.

I love cities, their complexity and energy. The belief that I might be able to shape and impact the urban built environment drew me to architecture. I have not been disappointed.

Each new building commission is a process of education, analysis, creation, invention, discipline and perseverance—where we attempt to build on the existing context, whether that context is physical or something less tangible. My real interest lies in the environment at large where architectural gestures can reverberate with public meaning.

When the interests of the architect and the aspirations of the client merge—when you are successful in solving the problem posed, satisfying the functional requirements, and are then able to create spaces and places, that lift spirits, stimulate the individual, foster interaction and create a sense of community and civic pride—the work is magical.

The creative forces within this city—cultural openness and unharnessed ambition —have certainly provided me opportunities to test my own creativity and professional imagination. So, in accepting this honor, I want to first thank my adopted home—Los Angeles.

I also want to thank my patrons and mentors, who personally nourished and supported my talents over the last three decades. Each of us, and most especially architects and artists, benefits from a patron and valued mentor, and I have been fortunate to have found both in my career.

And finally, the creative force that enriches me, in addition to my family, is the community of colleagues and friends whose own work engages and inspires me to continue to affirm the continuity of our history, celebrate our diversity, and invest in and repair the civic texture of our city.

Thank you to the LA Parks Foundation and all of you who are here today for this deeply appreciated recognition.

- Log in to post comments