For a broader planning perspective on Los Angeles’ new housing initiatives, and to gauge the private development community's reactions, The Planning Report met with Dan Garcia, who served 12 years on the Los Angeles Planning Commission, including ten as the Commission’s President. He is now a partner in the law firm of Munger, Tolles, and Olson, where he represents both for-profit and non-profit developers.

“The ‘housing lobby’ has been remarkably self-serving and narrow in their approach to issues.”

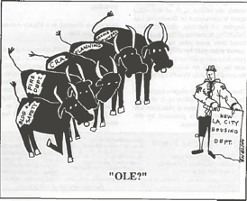

What expectations do you have for the City’s new Housing Department?

My hope is that the new Housing Department can facilitate the production of low-income housing rather than becoming just another regulatory agency that tries to gouge private property owners as they go through the approval process. It’s way too early to tell what the orientation of the new agency will be. I’m afraid, of course, that the Commissioners and others who interact with the Commission will see it as a political stage to promote their own careers, but the jury is still out.

How will the Department function on the intergovernmental relations level? How do you see it working with the CRA, Building and Safety, the Housing Authority, Planning, and so on?

Many years ago when I first became President of the Planning Commission, I observed that there was no continuous dialogue among COD, the CRA, the Housing Authority, and Planning, all of whom had joint responsibilities and common interests. I failed miserably in my attempt to make them speak to each other.

One of the rationales for this agency is that it will encourage that dialogue to occur, and they may have a better chance of succeeding. But on the other hand, they’ll never be given sufficient jurisdiction to deal with the problem.

It could be a frustrating experience for the Department to find that people essentially don’t care about low-income housing. When you talk about low-income housing, people in South Central will oppose it, people in East L.A. will oppose it, people on the West Side will oppose it whenever it is in their backyards. It’s not pleasant, but it’s true.

What has to happen to establish a good working relationship between the Housing Department and the Planning Department?

That’s a very troubling issue because the Planning Department is subject to a different set of political pressures than the political pressures which caused the formation of the Housing Department.

The departments inevitably have to collide—if you want more subsidized housing that implies more construction. And for that to happen some change will have to occur in a political system designed to prevent such change (i.e., growth) from occurring.

What are some of the impediments to the large-scale development of affordable housing in the city?

The main impediments are two-fold and the Department will have no effect on either. First are what I call the economic impediments. Those have included interest rates, which obviously has great impact on the housing market and the tax structure which has been changed in a way that discourages private investment in multi-family housing.

The second constraint is the arbitrary reduction in the amount of potential housing due to regulatory actions, primarily downzoning. The “housing lobby” has never taken an active role on this issue. In the city 75% to 80% of the land is dedicated to open space and single-family residential uses. This means that the rest of the land base has to support all of the commercial, multi-family residential, and industrial activity.

The transitional areas have been the subject of the planning wars of the last 10 years, and in almost every instance the potential supply of housing has been diminished by actions such as downzoning and interim control ordinances.

Might what you call the “housing lobby” begin to make a more active case for increased density in the city?

No. The “housing lobby” has been remarkably self-serving and narrow in their approach to issues. They never appeared in front of me once in the 12 years I was on the Commission to make any pitch other than, ‘I want more low-income housing.’

They want fewer units, higher quality, more recreational space, and lower rents. Frankly, those things are impossible to achieve simultaneously.

I would think that now, having been given more political support and no longer being separated from the process, maybe they’ll begin to rccognize some of these underlying tensions.

Is there adequate funding for a new housing department?

No. There’s no money. The city and the economy in general may be headed for a significant recession. The aerospace industry is beginning to destabilize, the furniture industry is essentially destroyed, and there will continue to be a massive diminution of construction financing because of the economic slowdown and new S&L regulations.

The whole strategy of low-income housing construction is dependent on continued economic growth. If you stop that part of it, then you’re left with nothing because there’s no constant source of federal or state revenues. There’s no money sitting around for housing absent the imposition of further fees on developers.

What is the outlook, then, for the linkage fee?

The Ninth Circuit Court is currently considering the Sacramento housing linkage fee ordinance. The City of Sacramento won at the trial court level and it’s on appeal now. The same consultants that did the nexus study in Sacramento are doing L.A.’s study, so we’ll learn a lot about the viability of the L.A. study from the outcome of the Sacramento decision.

Regardless, I think you will see some private property interests attack the linkage fee. I personally think that a linkage fee is desirable and certainly needed. The critical question is for government to make sure that the amount charged isn’t above what the market can afford to pay. This, unfortunately, implies an underlying rationale usually absent from the highly political land use approval system.

Assuming the fee is upheld, what agency should have jurisdiction over spending that money?

In Central City West, the view of everybody—Council offices, developers, and the community—was that no present city agency had the talent, energy, or history to be responsible for spending the fee money in the time frame they had in mind.

The City is frankly very slow—every contract has to be reviewed, there’s a million regulations, plus the question of whether you have to impose Davis-Bacon prevailing wages. So in Central City West you’re likely to see the creation of a separate entity—a housing corporation in which the city plays a strong role. From the perspective of private developers, simply handing over a whole bunch of money to the city will not achieve a rapid solution to our housing problems.

Is the non-profit community in Los Angeles ready to undertake such a largescale effort?

I bluntly think that a fair number of nonprofits don’t know what they’re doing in terms of the entitlement process and actual construction and maintenance of low-income housing. Some of them do, but I hope the non-profit lobby understands that there’s a need for some participation from ordinary profit-making developers if we want to make serious progress in the subsidized housing market.

How does the private sector view the role of the CRA on housing?

Everybody knows that public pressure is being put on the agency to act more directly in housing. The question I have is whether they have the resources to do the job in the scale that people are envisioning. I think there will be a shortfall, but they should be able to build a large number of units of reasonably high quality. The question is whether that amount will satisfy their critics.

Where should CRA 's housing funds go—should they go to low-income housing, should they be spread to accomplish other goals?

That's the South Park issue. Initially the CRA found itself in a trap—by allowing the C-2 zoning in South Park, land costs escalated such that even market rate housing was infeasible without subsidies. But that was before the cutbacks of the Reagan administration exacerbated the housing crisis.

Today it’s hard to justify using tax increment or other public dollars to subsidize market rate housing. Instead, the focus for market rate housing in CRA areas should be on being more flexible on densities for housing of commercial or retail projects.

Is there a future for a mixed-use ordinance in this city?

No. You can’t mandate what the market will accept, and more importantly, the distinctions between uses are so pervasive in our codes—in building and safety as well as planning—that it would take a lifetime to figure out how to remove them.

To give you an example, we represent a client seeking City approval for a mixed-use project with a small amount of retail and market rate condominiums. We need 19 separate discretionary approvals from the City. Building and Safety informed us they did not recognize the concept of shared parking without which you cannot have a mixed-use project. The Planning Department, ever helpful, forgot to publish the MND, causing weeks of delay.

The process, despite lots of political support, has been a nightmare. Simply having an ordinance saying “Thou shalt have mixed-use” on the planning side is nice, but unless you fundamentally change the extremely bureaucratic and regulatory nature of our planning and building and safety processes, you really haven’t achieved that much.

- Log in to post comments