At the dawn of the Los Angeles March 5th Primary Nominating Election, TPR is pleased to offer the following exclusive interview with Miguel Santana, Chief Administrative Officer for the City of LA, on the fiscal challenges facing the next administration. With spending growing faster than income, caused largely by pension and health-care costs, Santana forecasts a cumulative deficit of $1.4 billion over the next four years. Though some progress has been made, Santana notes that the scale of the fiscal situation means the next Mayor of Los Angeles will be confronted with a familiar challenge: making cuts while generating new revenue.

Miguel Santana

When we hire someone from the outside, we have to be able to make a commitment to that person, not just on the day they start but until the day they die. That’s a long time to make a commitment to somebody. So to a kid who has just graduated from college, I have to be able to say, “I can afford you today, and when you retire fifty, sixty, seventy years from now, I’m still going to be able to afford you.” -Miguel Santana

The CAO, your office, in February released a report on the City of LA’s fiscal condition entitled “City at a Crossroads.” Please summarize your findings.

Miguel Santana: We’ve made significant progress managing the city’s finances by resolving over 80 percent of the structural deficit. Four years ago we projected a cumulative deficit of over $1 billion on July 1, 2013. That deficit is now down to $215 and shrinking. We now have a healthy reserve fund as opposed to two years ago when we were downgraded twice because we were relying on our reserve fund to end the year in the black. We have reduced our dependency on one-time revenue to close our on-going budget holes.

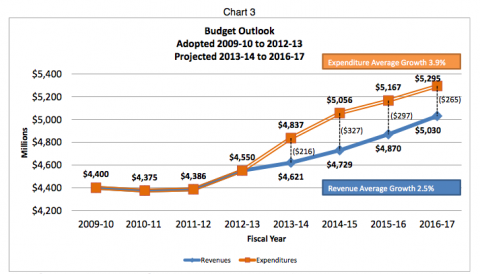

Our revenues are also growing by 2.5 percent. The challenge is that our expenditures still continue to outpace our revenues. While we reduced the number of positions by over 5300; adopted a new pension tier for both our new civilian and sworn employees; renegotiated our contracts so that city employees went from paying nothing for retiree health care to paying four percent of their salary for that same benefit; eliminated departments and consolidated others to reduce redundancies, we are still confronting a structural deficit.

Should Measure A not pass, the half-cent sales tax increase initiative, the greatest challenge the next mayor will confront is figuring out how to close a budget, year after year, while maintaining the current level of public safety while investing in the city’s infrastructure like our streets, technology, and buildings. Meeting both of these challenges will be very difficult if the next mayor relies exclusively on the natural growth of revenue through economic growth without having to make further cuts in spending.

Reading between the lines of the “City at a Crossroads” report, your office affirms that the “Security provided by the report’s optimistic picture is still very fragile and not an accurate reflection of the structural problems that the city is facing. As long as “growth and expenditures,” as you just said, “outpace increases in revenue, future budgets will still rely on one-time revenue to close in the black, leaving little room for addressing service gaps, investment in the city’s infrastructure and adequate reserves, to mitigate looming legal and unforeseen problems.” Please elaborate on your ‘citizen-beware’ warning.

We know we have some major liabilities floating out there. We have a potential lawsuit of hundreds of millions of dollars on the quality of our sidewalks and the allegation that they’re not ADA compliant. We have a lawsuit against our utility users tax that could be, best-case scenario, only about $20 million, worst-case scenario, up to $70 million. We know that our infrastructure is crumbling—our buildings, our streets, our technology. We also know that in terms our staffing levels, while we’ve reduced the number of positions, we haven’t necessarily reduced them in a strategic way. We did it out of crisis.

So how much of this is sustainable? No organization can survive, let alone thrive, if it’s not prepared to deal with liabilities that it knows it has floating out there; if it can’t manage it’s people effectively because it has reduced its capacity in a hurried, rather than strategic way; and finally, if it can’t invest in its infrastructure. So it’s not just about revenues growing. The economy is growing; we’re experiencing a recovery that is, frankly, fairly optimistic. But the question is, is that enough? What we have proposed is that in order for the city to thrive in the future, it needs to change the business model altogether. Its not just about taxes and cuts.

Could you elaborate on your reference to the city’s making “hurried” rather than “strategic” fiscal and management decisions the last few year? For example, there have been significant cuts in ‘positions’ with the city, as opposed to ‘jobs’. Have positions and/or jobs been strategically or hurriedly eliminated in an attempt to reduce budget expenditures?

Our approach has been, if an employee vacates a position, the position is likely to be eliminated. It is like assuming that what you’ve been doing must not have been important. Instead of setting priorities, deciding which roles and jobs are the most important to keep and which are not as important. We’ve done some of this, but not enough. Due to the crisis, so our goal has been to shrink quickly.

Isn’t it also true that when you now go to replace a position—assuming the mayor, the CLA, and you sign off on a new position—it costs the City more because of the contracts in existence now than it would cost you if you had not eliminated the position?

That’s correct. When we hire someone from the outside, we have to be able to make a commitment to that person, not just on the day they start but until the day they die. That’s a long time to make a commitment to somebody. So to a kid who has just graduated from college, I have to be able to say, “I can afford you today, and when you retire fifty, sixty, seventy years from now, I’m still going to be able to afford you.” A city employee is entitled by state law to the package of benefits that they sign up for on the day that he or she starts. Our ability to grow in the future has to be mindful of that.

When I talk about changing the business model, the city has to decide what it can do and needs to focus on doing those things really well. Then the city can decide what it can’t do, but saying, “Whom can we partner with to still do those things and to deliver services in a different way?” The most difficult part of this process is being willing to define what it is we won’t be doing anymore, period.

What real authority do the City’s elected leaders have presently to address LA’s structural deficit. The five year collective bargaining agreements negotiated with city unions in 2007 gave many city workers more than 25 percent pay hikes over five years (these contracts will be negotiated again in 2014). Are these contracts not binding? As for pension benefits, some city employees are able to retire with up to 100 percent of their salaries, a benefit unheard of in the private sector. What constraints do those five year contracts impose on how the city is able to address its structural deficit?

We’ve renegotiated those contracts twice, and it was through those renegotiations that city employees went from paying nothing for retirement and healthcare to paying four percent of their salaries towards that same benefit that used to be provided for free.

Are these increases in benefit contributions only for new employees?

No, current employees. Currently, employees used to pay six percent of their salary towards pension and retire health care—now they pay 11 percent of their salary. Four percent of their salary now fully pays for retiree health care—a benefit employees used to get for free—and one percent went to pay for the half of the early retirement program.

There are other reforms that we could do that have nothing to do with pensions. We could eliminate bonuses that are pension-based. We could require city employees to start contributing towards their current health care today. Most city employees pay nothing toward the health care premium while most Americans pay over 25 percent of the health care premium.

As to what we can do around pensions, we’re limited not just by the contracts but also by state law. We adopted a new pension tier, which is the most expansion in the state, For the first time city new city employees will have to pay half of the unfunded liability. That means if you have a 401K plan, when the economy does well, your 401K does well. Generally, when the economy doesn’t do well, in the private sector, you lose money; in the public sector, it doesn’t matter because the government makes up the difference so you never experience a loss. We changed that for new employees so that in the future, when the economy doesn’t do well, new city employees will have to make up half of that difference. We’re the only place in the State of California that has done that.

But is the City is hiring any new employees?

There are still some, and we still hire based on the fact that we lose over a thousand employees a year through retirement and other reasons. With many of those employees who retire, we eliminate those positions after they leave. But as the economy improves, and it will, the city will start hiring again. If we’re making a lifelong promise every time we hire someone, why would we make the same promise as we did in the past knowing that it’s not sustainable?

We have to start from somewhere. The challenge for the next mayor will be ensuring that the new pension tier that was adopted by the council isn’t unwound under the next round of negotiations.

LA City Councilman Bernard Parks recently wrote a response to your "City at a Crossroads" report, noting: "The City's number one problem is its inability to sustain and maintain its personnel costs. Our local government's addition to hiring personnel and maintaining a workforce in which the size and cost are not sustainable is the root cause of its ongoing structural deficit. The salaries, but more specifically the overhead (medical, pension, workers' compensation), costs are growing well above the real and/or projected revenue increases." Is he correct? And how opposed is the Coalition of City Labor Unions to the contract amendments that were adopted last year and that you'd like to see expanded in 2014?

At the end of the day, there’s only so much money. The challenge that the next mayor and the seven new council members will confront is how to deliver a level of service that the public demands while remaining solvent. That reality doesn’t change. What we need to do now is figure out how we maintain a more sustainable path in the future. How do we start getting away from year-to-year survival to actually investing and helping build the economy that we want to see in the future?

Let’s evaluate the last four years in light of the fair and favorable comments in the report. What would have happened if four years ago the mayor and council had demanded 10 percent across-the-board pay cuts and had proposed a half-cent sales tax for four years? Where would we be today?

We wouldn’t have a shortfall. A 10 percent cut across the board would have been a significant reduction to the structural deficit, as long as it was maintained and ongoing. While we essentially did that through furloughs it was a short-term strategy in saying…

But it must be noted, the City Council and Mayor agreed to a 25 percent wage increase.

That’s right.

How do you evaluate how the City’s elected leadership has managed LA’s fiscal affairs the last four years, which have been the toughest fiscal years in most of our lifetimes? Is not immediately implementing a ten percent cut in personnel, coupled with agreeing to a 25 percent, four-year wage increase for the Coalition of City Labor Unions, what will be remembered for years to come?

I think it’s a mixed legacy. Once a contract is set in stone, all we can do is ask the unions to renegotiate, and they can say no. We were successful in renegotiating their contracts twice and were able to gain one-time and on-going concessions; some of these solutions resulted in reducing the structural deficit by 80 percent. We can’t control the global economy, so when the recession hit, we saw all of our revenues drop by double digits. We are now seeing revenues grow again.

In light of all that, the city has survived. I know of no other city that has made adjustments as quickly as we have and managed to survive while so many talked about bankruptcy. I talk to my colleagues from around the country on a regular basis, and they’re shocked at what we’ve done. Is it good enough to just live another year? Is that really the goal? To be honest, for the last four years, that was the goal. I always thought my performance evaluation should be based on whether or not I ended up in bankruptcy court because my job was to make sure we didn’t end up there. We’ve succeeded in that, but is that the way to run a city? Of course not. No organization should be run to survive day-to-day, month-to-month, year-to-year.

The question about future negotiations is a critical one in terms of getting from the status quo of simply surviving, to actually reaching a place where we’re thriving. The same thing goes with new revenue. It’s going to take both of those efforts. It’s not just about controlling the expenditures side anymore; it’s not just about increasing revenues. It’s about doing both, concurrently.

Some have said, in light of Proposition A on the City ballot March 5, that labor’s historically preferred solution—more revenue, suggests that passing Prop A before the contract negotiations commence in 2014 eliminates any incentive for the coalition to actually accept next year any efforts that require labor sacrifice to close the City’s structural deficit.

There’s a difference between leverage and political will. If there’s political will to put us on a permanent, sustainable path, then you don’t need leverage because that’s ultimately what your end game is. So the question is, is the only way we get leverage by being on the brink?

Has not urgency over the past three years been your premise for the need by the Coalition to compromise with the City?

It’s certainly created a sense of urgency in light of that crisis, but part of a healthy relationship with labor or with any interest is to ask: “where do we really want to end up? Is this enough?”

What more can be done in the way of pension reform, given the political will?

Right now, our number one priority is to maintain the pension reform that’s been adopted.

What’s the number one goal of the Coalition of Labor Unions?

They’ve made it clear that they intend to challenge the pension reform that the city has adopted for new employees. They think it goes too far. This is a multi-billion-dollar debate. The new pension tier, as established by outside actuaries, will save us $4 billion in the next 30 years.

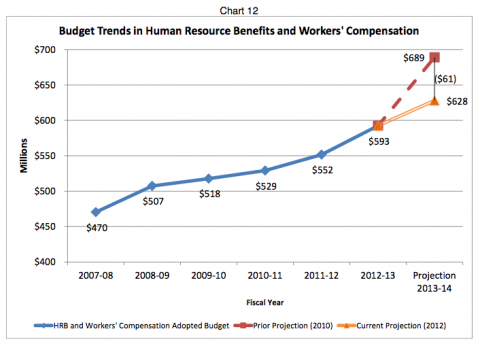

Pensions are incredibly complicated. You tweak one portion and it has a ripple effect for generations, both in cost and savings. Any discussion around pensions for the future has to be mindful of that. You can see the progress that we’ve made already. Our pension costs are still growing, but they’re not growing at the same rate as we had originally projected, in part because of the reform that’s been adopted. We had projected that our pension costs would be close to $1.3 billion on July 1. They’re at a billion, so there’s a $300-million difference in that projected cost, much due to the fact that we’ve adopted some reforms already, on the civilian and on the sworn sides. If we start unwinding that, then our pensions will continue growing at a higher rate than they currently are. Then promises that we make to a 22-year-old kid who graduates from college and works for the City of Los Angeles will be very difficult to meet.

Much about pension reform is really about ensuring that city government is still in a position to deliver on that promise. That is why we share a mutual responsibility in ensuring that our pensions are sustainable.

In terms of political will, what is your estimate of the city electorate’s political will going into 2014 and into those negotiations? What will this spring’s city election results tell you about political will in 2014?

I think that the election is not really a bellwether in the way that people may read it. No candidate will come in with a mandate of one form or another. The mandate really comes from the elected officials themselves. They will provide direction as to what outcomes they want to achieve, and will need to stand firm on achieving that outcome.

Do you think present city leadership thinks of the city more as an employment agency than a service agency?

There are some who think our job is to keep as many people employed as possible, and there are some who evaluate our success by the outcomes we produce. I think, at the end of the day, we’re all public servants—we are elected or appointed—and we’re here to provide exactly that, a public service. Our jobs are not to keep our jobs; that’s not what being in public service is about.

In terms of the service delivery, what percent of the City of LA’s general fund and the budget is for police?

Over 70 percent goes toward police and fire.

So if one mayoral candidate’s proposal to increase the department by 2000 officers were to be approved, what would that mean for the rest of the City’s service delivery system going forward?

Well, it means that that’s basically all we will be doing. If you’re going to siphon off more of our revenue to expand the police force, then there are only two questions you have to answer: what is it you’re not going to do anymore, or, what revenue are you going to raise? Either you cut or you get more revenue. That’s certainly the prerogative of the next mayor, to have specific policy goals and objectives. He or she will need to build a consensus around not providing other services anymore or needing to have a new revenue source to expand the police force. It really comes down to those two basic questions. It’s not complicated.

Two last questions. You spent much of your early career with the County of Los Angeles. The County’s fiscal situation seems to be significantly better than the City of LA’s. How do you compare and contrast the political will or conditions that allow for that to be the case?

Two words: term limits. You know, most of the members of the Board of Supervisors served during the early 90s when the county confronted many of the same problems we’re confronting now at the city. I believe that their experience really formed their view on fiscal policy and management. So it’s not surprising that most fiscally conservative members of the Board of Supervisors are actually liberal democrats. They are much like the great depression generation, where they say, “We’re never going back there again.”

The most telling experience of that is when the state, cities, and counties were changing their pension system to three percent at 50—Gloria Molina, Yvonne Brathwaite Burke, and Zev Yaroslavsky, Mike Antonovich and Dean Dana stood firm against that current, despite the fact that there was tremendous political pressure and talk by labor about having candidates run against them. They, in some ways, had the crystal ball that many cities and counties and states around the country now wish they had had, and that allowed them a level of fiscal constraint that helped the County weather the storm.

The other big change in policy that they’ve stood firm on: spending one-time money on one-time items. When there is economic growth, you shouldn’t assume that growth will exist forever. At no time in human history has the economy grown forever. There’s always a recession. They are smart in investing one-time revenue in buildings, cultural institutions, and infrastructure. Many structures around the county have been built or strengthened using one-time revenues. People are shocked when they hear that LA County+USC Medical Center, as an example, is paid for. After the debt was issued, they saved enough money and paid it all off. Those are smart things to do when you have increases in one-time revenue. The worst thing you can do is to assume the economy will grow forever and build the size of government based on that assumption. It’s a cautionary tale as we move forward.

The truth is, the economy is getting better. You can feel it; you see it in our revenues. The question that we raise in our report is, are the next mayor and city council members going to ignore the mistakes of the past and fold to the pressure to restore services and be generous in the next round of labor negotiations? Or are they going to exercise some level of fiscal constraint, invest in our infrastructure, while being responsible as an employer?

Miguel, you’re only 43, and yet you’ve had a world of experience in government, and you’ve spent some time at the Kennedy School. What could you do next? What do you want to do next?

You know, I’ve been fortunate. Right out of college, the first job I applied for was with Pomona College. I worked there for a few years in admissions. I haven’t applied for a job since. So I’m a big believer that I’ll end up where I need to be. Part of the fun of living is not knowing where that’s going to be, but I know that wherever that is, I’m going to be enjoying it and making a contribution, as I am doing with this job.

Thank you, Miguel. The City is the better for having you in this job.

- Log in to post comments